It will be 30 years since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake on January 17, 2025. In November last year, Kobe University established the “Committee for the 30th Anniversary of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake” with President FUJIWARA Masato as its chairman, which will work for over a year to disseminate research results as well as utilize and pass on documentation of the earthquake.

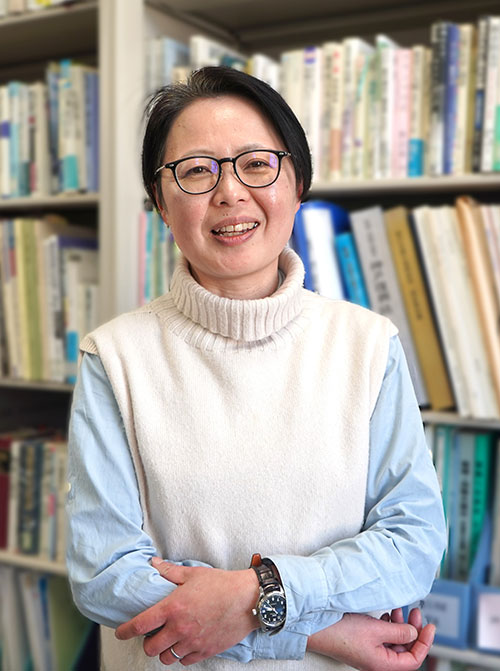

How can the knowledge accumulated in the 30 years since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake about major disasters both in Japan and abroad be applied to the future? We interviewed KONDOU Tamiyo, a professor of the Research Center for Urban Safety and Security at Kobe University, specializing in residential environment planning, disaster mitigation and recovery studies. We asked her about the 30 years since the earthquake, future research and lessons to be learned from the disaster-stricken city of Kobe.

You were a first-year student in the Department of Construction at the Faculty of Engineering when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck.

Kondou:

At the time, I was living alone in Higashinada-ku, Kobe, but I happened to be at my parents’ house in Shiga Prefecture when the earthquake struck. I believe it was about a week or ten days later when I first went to university after that. I already had seen images of the collapsed JR Rokkomichi Station on TV, but was shocked to see the actual collapsed houses, warped buildings and roads.

I think it was some years after the earthquake that I heard from Professor MUROSAKI Yoshiteru of the Faculty of Engineering (now a professor emeritus), and what he said left a strong impression on me. He said, “We have taught students how to build, but not how buildings break.” I thought that was certainly true. We learn how to “build safely,” but we never learn how they break and until the earthquake, we never had a chance to actually see them.

Bereaved families leave living proof of their deceased family members

Did the earthquake trigger your interest in disaster research?

Kondou:

I did not set out to do research on disasters. After the earthquake, there was a conflict between citizens and the government over urban planning. Seeing this, I wondered why the citizens were so angry, and I felt the difficulty of city planning. What interested me then was the role of experts who act as intermediaries between the government and residents. In my graduation thesis, I examined the role of experts with regard to a road that the Kobe city government had planned in the 1960s and that local residents continued to oppose even after the earthquake.

I entered graduate school not because I wanted to become a researcher, but because I genuinely wanted to know and conduct research in the field. My research theme was not the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, but rather urban planning in the U.S. and England. My research advisor, Professor SHIOZAKI Yoshimitsu (now a professor emeritus), had translated a book on community-based urban planning in Europe and the U.S. and I wanted to conduct on-site research in the U.S. At the time, I wanted to become a consultant for urban development.

When you were a student, you participated in the “Victim Interview Survey,” which was initiated by Kobe University in 1998. This is a valuable survey that records a comprehensive picture of the earthquake by asking families who lost family members in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake about the layout of their houses and how they were affected by the disaster.

Kondou:

I volunteered to participate in the survey. Looking back, I think I had a sense of the problem of houses being destroyed and the ensuing loss of life. I thought that keeping a record of why so many people died was fundamental to considering safety. However, Professor Murosaki, who proposed the survey, assured us that it was not for dissertations and also for me it was a separate activity from my research. The survey has been passed on from one generation of Kobe University students to the next and, with the approval of the bereaved families, the records have been made public at the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution (in Chuo Ward, Kobe City).

The bereaved families who responded to our survey expressed their strong desire to “leave living proof of their deceased family members.” I felt that although they were carrying painful feelings, they were by no means weak. I think this experience is one of the things that shaped who I am today.

It is impossible to control people through urban planning

After the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, are there any other particular disasters that you have been involved in researching?

Kondou:

Hurricane Katrina (2005), which severely damaged New Orleans in the United States, and the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011). At the time of Hurricane Katrina, I was a senior researcher at the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution. I was approached by a researcher at the Disaster Prevention Research Institute of Kyoto University, where I had been employed prior to joining the Center, and I began visiting the sites. It was around that time that I began to engage in full-fledged research on disaster recovery.

I was pregnant at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, and it was one year after the disaster that I arrived at the site. I felt that it would take at least 10 years to recover from the disaster. Although I have not been involved in research on the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I have continued to visit the affected areas in East Japan, perhaps subconsciously thinking that I am providing redress for what I could not do in Kobe. I entered Otsuchi Town in Iwate Prefecture, an area affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, with volunteers from among the students in my own seminar and continued to observe the activities of these students and local high school students who were making fixed-point observations of the recovery. I thought that if I could help with the recovery, this would be achieved by thinking together rather than by conducting research. These activities are now being carried out independently by high school students in Otsuchi.

On the research side, we conducted surveys on housing reconstruction in Ishinomaki City in Miyagi Prefecture and Rikuzentakata City in Iwate Prefecture. As is the case in East Japan and New Orleans, what I feel from my research so far is that it is impossible to control people through urban planning. The disaster victims are not waiting for a reconstruction plan to be developed before deciding where to live. The basic idea of urban planning is that if people are not controlled by planning, they will move as they wish and there will be no order. I feel that such a sense of planning as a panacea is highly questionable. I think we need both freedom and the control.

It seems like a theme that gets to the root of disaster recovery.

Kondou:

I believe it is important to have the ability to adapt and understand the free movement of disaster victims, rather than focusing solely on resilience and improvement which proceed into a single direction. In the Great East Japan Earthquake, areas inundated by the tsunami were designated as disaster risk zones and construction is now restricted. However, there have been cases where disaster victims themselves have turned vacant lots into community farms or places where they can talk with their deceased loved ones, thereby reconnecting with the communities where they used to live. This is reconstruction placemaking, or in other words, the rebuilding of places. I think these movements are examples of the adaptability of disaster victims.

However, we are seeing various distortions in the current approach to reconstruction, and I believe that the method itself must be fundamentally changed. How to change it is yet to be seen, but for a huge Nankai Trough earthquake or a mega earthquake directly under the Tokyo metropolitan area, the system of reconstruction itself, which was assumed in Hanshin-Awaji and East Japan, needs to be changed. In other words, I believe that we must conduct research on pre-earthquake reconstruction. I think it is necessary to look at things through a different lens, based on the accumulated experience of city planning in ordinary times.

I understand that you also visited the areas affected by the Noto Peninsula earthquake that occurred on January 1. From what perspective do you view this disaster?

Kondou:

Even before the Noto Peninsula earthquake occurred, I had begun research on the theme of mobile homes and multi-regional residence. Japan is characterized by the fact that many people live in the same place all the time and have low mobility. While this is important for the formation of towns and cities, I believe that more people may move around and live in multiple locations in the future. I believe this perspective is also relevant to disaster research.

Having a base or relationships outside of one’s primary area of residence in one’s daily life may lead to the option of taking temporary shelter there in the event of a disaster. It may also reduce the resistance to migration and enable continuous housing recovery. I feel that having multiple locations will lead to a resilient and adaptable lifestyle that will also contribute to advancing recovery.

I visited the Noto Peninsula earthquake-stricken area in early March, about two months after the occurrence of the earthquake. Many of the victims had moved from the heavily damaged Okunoto area to a temporary evacuation center (Ishikawa Sports Center) and secondary evacuation centers (hotels, private accommodations, etc.) in Kanazawa City.

Where to rebuild their homes and how to reconstruct their lives are the issues that the disaster victims are struggling with the most. Regarding such housing reconstruction issues, I believe that in a society with a declining population like today’s, it is necessary to develop support measures based on the premise of residential mobility. I believe that we need to provide support that takes into consideration the well-being of people who are relocating from their original areas, as well as pursue the reconstruction of villages and towns that can be sustained even in the face of a significant decline in population.

Every academic discipline should be able to contribute to disaster relief

What are your plans for the 30th anniversary of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake?

Kondou:

I think we will not be able to see the future unless we start by looking back. How has each academic field evolved? As a university in a disaster-stricken area, I think we must consider this. Not only research directly on disasters, but also medicine, education, economics, law, and other academic fields can all make some kind of contribution in times of disaster. In the past 30 years, there have been remarkable advances in information systems and other technologies. I believe that if people from diverse fields are connected, they will be able to find solutions to problems that cannot be solved by their own field alone.

At Kobe University, whenever a disaster occurs somewhere, the topics of “when to go to the disaster area” and “how to support the victims” are immediately discussed. Student volunteer activities for disaster relief have also been passed down from generation to generation. It might be called a disaster culture.

I think it is important to think together with citizens. The Research Center for Urban Safety and Security of Kobe University, to which I belong, has been holding open seminars open to anyone since 1997, and this year we will hold the 300th such seminar. I would like this seminar to continue to be a place where we can think together with citizens.

I was shaped by Kobe, and nurtured by various people such as disaster victims, planners, and government officials and so on. From now on, we must give back to the ongoing disaster-stricken areas and to “unaffected areas” that may be hit by disasters in the future. I hope that we can continue to increase the number of comrades who think together with us after the 30th anniversary of the disaster.

Resume

| March 1998 | Graduated from Faculty of Engineering, Kobe University |

| March 2003 | Doctor of Engineering from the Graduate School of Science and Technology, Kobe University |

| April 2003 | 21st Century Center of Excellence program researcher, Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University |

| April 2004 | Senior researcher, Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution, The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake Memorial |

| October 2008 | Associate professor, Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University |

| October 2022 | Professor, Research Center for Urban Safety and Security and Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University (April 2023- Vice-Director of the center) |