A new academic field called “atmospheric studies” is developing at Kobe University. We often use expressions like “good atmosphere” or “bad atmosphere,” but what does that really mean? Researchers from various fields both inside and outside the university gather at the Kobe Institute for Atmospheric Studies (KOIAS), a research organization established last year at the Graduate School of Humanities, to explore this question academically. We asked the school’s HISAYAMA Yuho, associate professor for modern German literature and the institute’s representative, about the current state of atmospheric studies and its future goals.

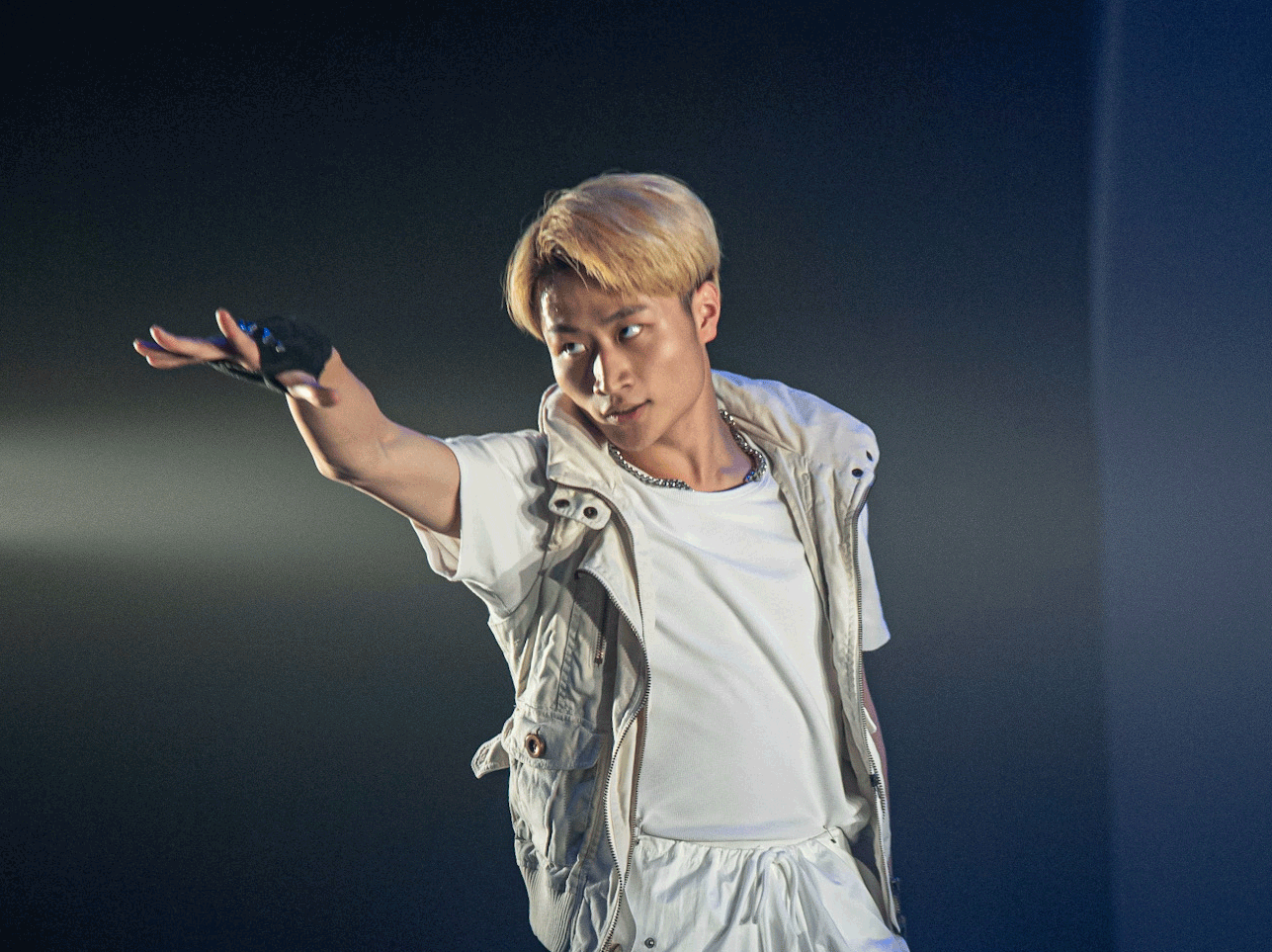

Associate Professor HISAYAMA Yuho

What is atmospheric studies?

What kind of academic field is atmospheric studies?

Hisayama: “Atmosphere” is a familiar phenomenon to us. We use expressions like “the spirit of the time,” “the atmosphere of the meeting,” and “the mood of the space” on a daily basis. However, when asked, “What is atmosphere?” it is difficult to answer. Our starting point is that we want to be able to treat this phenomenon academically. We want to verbalize an atmosphere that is difficult to describe, establish basic vocabulary, and create concepts.

In recent years, the number of researchers focusing on atmosphere has been increasing, mainly in Europe. However, researchers are scattered in various places, and they have not yet established a comprehensive new academic field.

The Kobe Institute for Atmospheric Studies is a network of researchers from various fields such as philosophy, history, literature, art studies, and architecture. I believe that this is the first cross-disciplinary research institute in the world that specializes in atmospherics. We are planning to develop research that goes beyond cultural and regional frameworks.

What kind of research are you specifically conducting?

Hisayama: This year, the Kobe University Press published a book called “Jinbungaku o Tokihanatsu (Liberating Humanities),” which was compiled by the Graduate School of Humanities. In the chapter on “Atmospheric Studies,” three KOIAS members including myself introduce several aspects.

One of these aspects that the institute is focusing on is architecture. For architecture and urban design, atmosphere might be a key element. What exactly are the “comfort of living” and “air of the place” that we often mention? We want to verbalize such “things that are somehow felt.” For example, some researchers are running a project where they ask people to take pictures of buildings, landscapes, and structures in the city that caught their attention and to write down what they felt. The researchers then use this to extract common adjectives and keywords to create data.

More broadly, we would like to further examine art in general. In contemporary times, there is a trend in art that is not just visual, such as appreciating paintings, but is felt with the whole body. It can be thought of as art tied to atmosphere. The institute is also working on cooperating with museum exhibitions. Art has an aspect of anticipating what could happen in future society, so we think it’s important.

Why did you focus on atmosphere in the first place?

Hisayama: In addition to being interested in the phenomenon of atmosphere, there is a connection with my research field. My current specialty is German literature, and I mainly study Goethe. Goethe is known as a poet and writer, but he was also a natural scientist. In his major work “Theory of Colors,” he discusses the impact of colors on humans. He mentions the “atmosphere of color,” saying things like “yellow gives a warm and comfortable impression” and “blue has a chilly feeling.”

Goethe also describes something that can be called atmosphere in his literary works. In his masterpiece “Faust,” there is a scene where the protagonist Faust sneaks into the room of Margarete, the woman he loves, and escapes, and when she returns home, she feels “something is different.” Even though there is no physical change, the atmosphere of the room has changed.

The German philosophers Hermann Schmitz (1928-2021) and Gernot Böhme (1937-2022) can be said to have laid the foundation for the theory of atmosphere through their study of Goethe. Schmitz published a major work on Goethe in his youth and later established a highly original philosophical system. Böhme, who was also a Goethe scholar, absorbed the results of Schmitz’s work and developed the study of atmosphere. When I was in graduate school, I studied abroad in Germany, and Böhme was my supervising professor. From the standpoint of having studied Goethe, I feel that atmospheric studies are not a new field for me, but rather an extension of these previous works.

Identifying commonalities beyond cultural and regional frameworks

You also talk about “ki” and “air.” This makes it seem like the research is being conducted in the East.

Hisayama: The theme of my doctoral thesis, which I wrote in Germany, was actually “ki.” The field of study is comparative literature and comparative thought. I published it as a book in German, but I expressed it as “ki” in Japanese. What I emphasized in this book is that “ki” is constantly interacting between the inside and outside of human beings, and it exists both inside and outside the body. In Japan, where there are expressions like “to exchange ki” (meaning “to get along well”), I think it is easily understood concept.

On the other hand, in modern Europe, it is common to completely separate the inside and outside of humans and consider individuals as “closed beings,” and this has become a basic assumption of modern society. Think, for example, about the relationship between the weather (in Japanese: the “ki of heaven”) and humans. No matter how sunny and pleasant (in Japanese: “having good ki”) the day is, or how cloudy and gloomy the day is, the judgment handed down in court by humans must not change. That is the human view and ideal image of modern times, isn’t it?

Even in the academic world of Japan, the thought model of modern Europe has become the norm. However, I believe that there are aspects of this way of thinking that can be reexamined to ask, “Is this really so?” There is something that falls through the traditional European model. Böhme, whom I mentioned earlier as a scholar of atmospheric theory, used expressions like “between subject and object” and “quasi-objectivity” as new ways of thinking.

However, while criticizing the modern European model, atmospheric studies should not lean towards orientalism or exoticism. Through dialogue with different cultures and fields, we want to clarify the commonalities and individualities concretely. Actually, if you look at the history of European thought, there are words like “pneuma” (Greek) and “Geist” (German) that are similar to “ki.”

It is often said that the culture of “caring about the atmosphere” and “reading the air” is unique to Japan. There is also the word “peer pressure.” How do you think about this?

Hisayama: The well-known “Study of ‘Air’” (written by YAMAMOTO Shichihei) writes about the reign of “the air” that is said to be unique to Japan. Yamamoto, who knows the air of the era when Japan plunged into war, discusses postwar society from various aspects based on his own experience. It is a widely read book, touching on examples such as different conclusions at formal meetings and later drinking parties.

From the perspective of Japanology, I think this point of view is interesting. However, academically, there are aspects in which it is insufficient. For example, was Japan’s totalitarianism different from that of Germany or Italy? Is what is said to be unique to Japan really so? I think it is necessary to look at it from a critical perspective.

I said that the modern European thought model has become the standard in Japan, but it is also important to look at the historical nature of this “modernity.” The word atmosphere was born in modern times. It started to be used in English and German in the 17-18th centuries. In other words, atmosphere can be said to be a modern concept.

However, it is not that there was no “experience of atmosphere” before the modern era and outside the world of modern Europe. It is in the pre-modern or non-European world that we may find hints of new ways of thinking.

For example, in Japan, the translated word “atmosphere” began to be widely used in the Meiji era (1868-1912), and there was no such word in the preceding Edo period (1603-1868). However, in the Edo period, there were various expressions such as the contrast of “refined versus ordinary,” “ki” as I explained earlier, “iro” (“color,” but also “mood,” “essence”), and “fuu” (“wind,” but also “manner,” “style”). We are focusing on such points and are broadly advancing cultural history research of atmosphere while comparing it with the present.

Becoming an international research network hub

Please tell us about the challenges for future research and the future image of the institute.

Hisayama: Atmospheric studies is a new academic field, but I think it is a theme that is currently attracting attention internationally. Perhaps because artificial intelligence, an intelligence without a body, is becoming a reality, a re-examination of the physicality of atmosphere is called for.

We tend to perceive “good atmosphere” as a plus, but we need to take into consideration points such as a good atmosphere possibly being the result of excluding outsiders. Also, there is a research challenge in the difficulty to digitize and quantify atmosphere. When one quantifies a specific aspect, it becomes something different. The choice of parameters is therefore also a theme to be studied. And we are also advancing joint projects with the Kyoto-based Shimadzu Corporation.

Over the past year or so, the institute has signed agreements with research institutions in Italy, Germany, Canada, and Slovenia. We are also considering an agreement with an organization in Taiwan, and we plan to invite researchers in philosophy and architecture from Italy. In the future, I would be happy if this institute becomes the hub of an international network and if people think “KOIAS” when they hear “atmospheric studies.”

Resume

| March 2006 | Graduated from the Faculty of Integrated Human Studies, Kyoto University |

|---|---|

| March 2008 | Completed the master’s program at the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University |

| April 2009 | Visiting researcher at the Institut für Praxis der Philosophie in Darmstadt (Germany) |

| April 2011 | Special researcher at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science |

| May 2013 | Received a doctorate from the Technische Universität Darmstadt |

| October 2013 | Lecturer at the Graduate School of Humanities, Kobe University |

| August 2016 | Associate professor at the Graduate School of Humanities, Kobe University |

| March 2021 | Received a doctorate from the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University |

| April 2022 | Representative of the Kobe Institute for Atmospheric Studies |