Freshwater carbon — CO2 that has been absorbed and accumulated in fresh water areas like lakes and reservoirs — is receiving attention for its potential contributions to achieving a carbon neutral society. Kobe University is a hub for freshwater carbon research, with Graduate School of Engineering Professor NAKAYAMA Keisuke, an expert in aquatic and environmental engineering, at the forefront. Relatively unexplored when compared to the “blue carbon” absorbed by the oceans, Nakayama realized the potential of freshwater carbon and has conducted surveys both in Japan and around the world. Also known for his research on the marimo algae balls in Hokkaido’s Lake Akan, Nakayama told us about the current state and results of his freshwater carbon research.

Field trials at reservoirs in Kobe rarely performed anywhere else in the world

What led you to begin your research on freshwater carbon?

Nakayama:

Research on how much carbon is absorbed and accumulated in lakes and reservoirs has been carried out around the world since about 10 years ago. Unsurprisingly, a growing interest in countermeasures for global warming was behind this research.

I had originally performed research on flow and waves of water, but around 2015, I met a Taiwanese researcher who performed observations on wetlands, something we had in common, so we decided to perform joint research on lake metabolism in Taiwan.

In papers published overseas in the 1990s, there was an established theory that “even though wetlands are an emission source of CO2, they aren’t CO2 sinks.” But I thought quite the opposite, that wetlands, with their abundant phytoplankton, are serving to absorb and accumulate CO2. Compared to the oceans, which spread out far and wide, lake water hardly moves at all, which I thought should allow it to efficiently accumulate CO2. After investigating the state of phytoplankton in natural lakes in Taiwan, we learned that CO2 from the atmosphere was being absorbed and accumulated in these lakes.

In addition, a connection I made during my time as a visiting professor at the University of Western Australia led to us starting joint research in which we measured the CO2 absorbed and accumulated by aquatic plants of a lake in Australia. Lake Monger, the target of our research, was known for its high concentration of aquatic plants, and the results of our research allowed us to elucidate that these plants were contributing to the absorption and accumulation of CO2 in the lake.

How about your surveys in Japan?

Nakayama:

We’ve performed field trials at Karasuhara Reservoir (Hyogo Ward), one of Kobe City’s water sources. These all started about five or six years ago, when I heard through a fellow researcher that Kobe City was intending to perform surveys and research on its fresh water areas.

Kobe City had always taken countermeasures to combat things like musty tap water and improve the water quality of its reservoirs, and staff at the Kobe City Waterworks Bureau have found that some of the bacteria found on aquatic plants prevents outbreaks of blue-green algae. So, after consulting with an expert in aquatic plants, we planted native pondweed in a reservoir and monitored the quality of the water as well as the absorption and accumulation of CO2.

Initially, however, the pondweed was being eaten by invasive species of turtle. These turtles were originally kept as pets but were released in the reservoir and lived there in great numbers. By simultaneously planting the pondweed and eliminating the turtles, we saw a marked increase in the pondweed and, as a result, we were able to confirm both improved water quality and the absorption of CO2. The field trials were exceedingly rare, even outside of Japan, which gathered a good deal of attention.

As surveys are carried out both in Japan and around the world, in 2023, I devised the name “freshwater carbon” to differentiate it from the blue carbon found in the oceans, and published it in a paper. I hope to disseminate this as an effective countermeasure for global warming.

Aquatic plants in wetlands as not a bother, but a boon

How much potential does freshwater carbon hold on a global scale?

Nakayama:

The total area of coastal regions that can store blue carbon is 1.8 million ㎢, whereas areas that can store freshwater carbon total 5 million ㎢, so I see freshwater carbon as having great potential for absorption and accumulation of CO2. Forests play a significant role in the absorption of CO2, but as trees age and their absorption rate drops, the role of freshwater carbon will become even more vital.

Wetlands are divided into categories based on the amount of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, namely oligotrophic (low nutrient level), mesotrophic (medium nutrient level) and eutrophic (high nutrient level). Through our previous research and surveys, we know that mesotrophic wetlands with rich biodiversity absorb and accumulate the most CO2, while wetlands low in nutrients and biodiversity don’t absorb or accumulate nearly as much. Earlier, I mentioned that in the 1990s, research from overseas showed that wetlands are a source of CO2, and it’s thought that the reason for this is that the surveys were done on oligotrophic wetlands.

However, even oligotrophic wetlands have the potential to absorb CO2 if we increase the amount of native aquatic plants and phytoplankton. This is a similar idea to movements to increase blue carbon in coastal regions by planting eelgrass.

For a long time, phytoplankton has been vilified as being the cause of red tides and blue-green algae. Those types of issues will occur if an abundance of phytoplankton is causing wetlands to become eutrophic, but we now know that phytoplankton actually serve an important role. Aquatic plants also tend to be thought of as useless since they get in the way of fishing and watersports, but I hope to get as many people as possible to understand that they’re vital to achieving a carbon-neutral society.

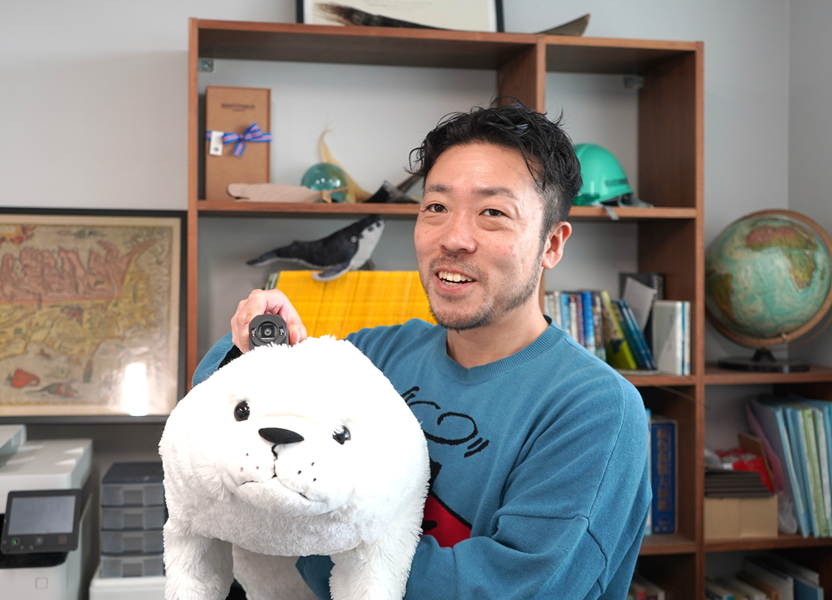

Outside of your research on freshwater carbon, you also continue to perform research on marimo algae balls, one of Japan’s special natural monuments.

Nakayama:

I began researching marimo during my time at Kitami Institute of Technology (KIT) in Hokkaido, which was before taking my position at Kobe University. KIT is located in Hokkaido’s Doto region, also home to Lake Akan, which contains the world’s only colony of giant marimo.

I came to this research group on marimo from my original field of “water flow,” or rather, fluid mechanics. Marimo are made of stringlike algae, but at the time, we didn’t understand the mechanisms of how they got so round and so big. Through our surveys, we found that marimo grow into balls by being spun around by forces of wind and waves.

After that, we surveyed the relationship between marimo growth and water temperature and discovered that marimo actually become smaller when the temperature of the water gets warmer. Recent global warming has created a dire situation for the marimo, which grow in cold areas. We’ve got to quickly think of ways to protect them.

The number of wetland researchers in Japan is on the decline

How will you continue your research on freshwater carbon moving forward?

Nakayama:

We’re planning on performing surveys using satellite data to get an understanding of the current state of our wetlands. In addition to Karasuhara Reservoir in Kobe City, we also plan to work with local researchers to perform surveys on Lake Akan, Lake Suwa (Nagano Prefecture), Lake Biwa (Shiga Prefecture) and reservoirs in Ehime Prefecture.

If biodiversity and water quality of wetlands improve, it will lead to an improvement of the environment of the oceans to which the water is flowing. It’s often said that the richness of the forests begets the richness of the seas, but I think the wetlands in between are also important. If we can determine the state of these lakes through these surveys, this will allow us to also develop effective strategies to improve them.

At the bottoms of these lakes, there are areas called “dead zones” which contain extremely low amounts of oxygen, but we still don’t fully understand the mechanisms behind why they form or disappear. I’d like to elucidate these mechanisms and create a system for monitoring lakes around Japan.

An issue we’re facing is the gradual decline in the number of wetland researchers in Japan. As long as there are no obvious issues to investigate, it’s difficult to secure funding to survey wetlands that are managed by national and local governments in Japan. There is huge potential in research on fresh water areas, so I strongly hope that many young researchers will get involved.

Resume

In 1992, graduated from the School of Engineering, Hokkaido University. In 1994, completed the master’s program at the Graduate School of Engineering, Hokkaido University. In 1995, became assistant at the School of Engineering, Hokkaido University. In 1998, received his doctorate in engineering from Hokkaido University. In 1999, became researcher at the Port and Harbour Research Institute of the Ministry of Transport. In 2001, became research fellow at the National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. In 2007, became professor at the School of Engineering, Kitami Institute of Technology. Also served as visiting researcher at the University of Illinois and visiting professor at the University of Western Australia. In 2015, became professor at the Graduate School of Engineering, Kobe University.