Creating fuel and chemicals from agricultural waste to revolutionize the industrial structure, that’s the aim of the cutting-edge biomanufacturing research activity based at Kobe University. One key player in this research is Professor OGINO Chiaki, a bioproduction engineering expert at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Engineering. Efforts in a joint research project with agriculture giant Indonesia to attempt to ease climate change and achieve clean energy are gathering attention. We asked Ogino about his ambitions regarding his research and his outlook on social implementation.

Utilizing wastewater from palm oil manufacturing to establish a bio-circular economy

Tell us about your current research.

Ogino:

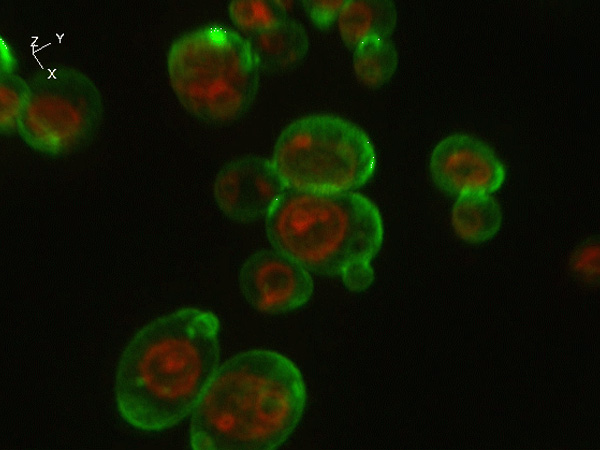

Our research aims to change biomass (organic, renewable materials originating from living organisms) into biofuel and chemicals through the power of microorganisms to establish a bio-circular economy. While we are considering using various agricultural waste as raw materials, we’re particularly focused on research and commercialization using wastewater gathered in the extraction process of palm oil. By harnessing the power of microorganisms, we can create biofuel, chemicals and plastic raw materials.

We’ll eventually exhaust our petroleum resources, and certain chemical manufacturing processes release greenhouse gases, a factor for global warming. There will definitely come a turning point where we break free of our current dependency on petroleum resources and focus our efforts on developing a sustainable society. Thus, I strongly believe that research using biomass is exceedingly important.

Technology and manufacturing that can create various products from biomass are called “biorefineries.” Our goal is to transform oil refineries into biorefineries, and we’re looking to create new chemical manufacturing and establish a bio-circular economy.

Why have you focused on palm oil? Also, why collaborate with Indonesia?

Ogino:

When producing biofuel and chemicals, the first challenge you need to consider is how you’ll secure raw materials. With its thriving agriculture, Indonesia is a country rich in biomass. Indonesia also has many palm plantations which produce large amounts of wastewater containing oil and fat components during the oil extraction process. But this wastewater isn’t being reused, which could lead to water pollution issues, so we’ve taken particular note of it as a raw material.

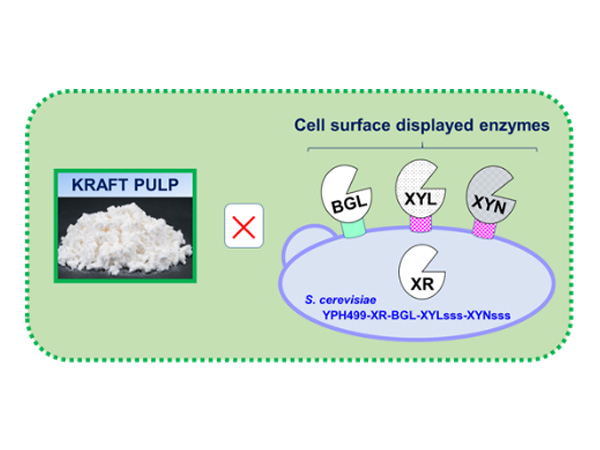

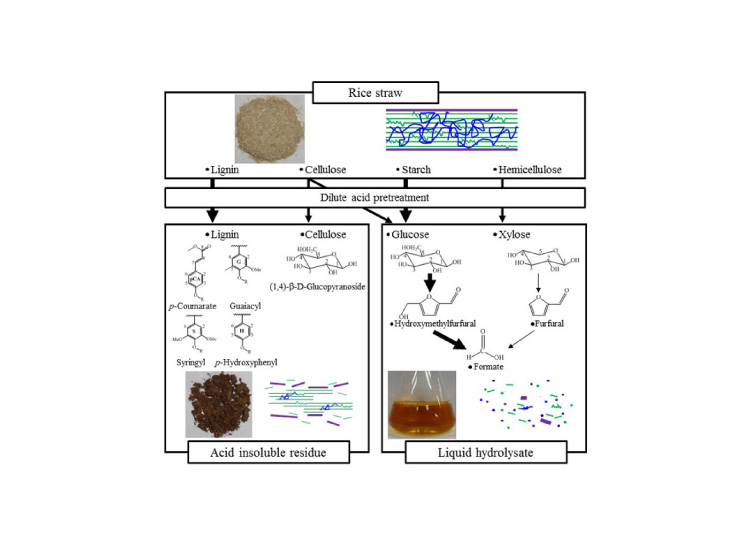

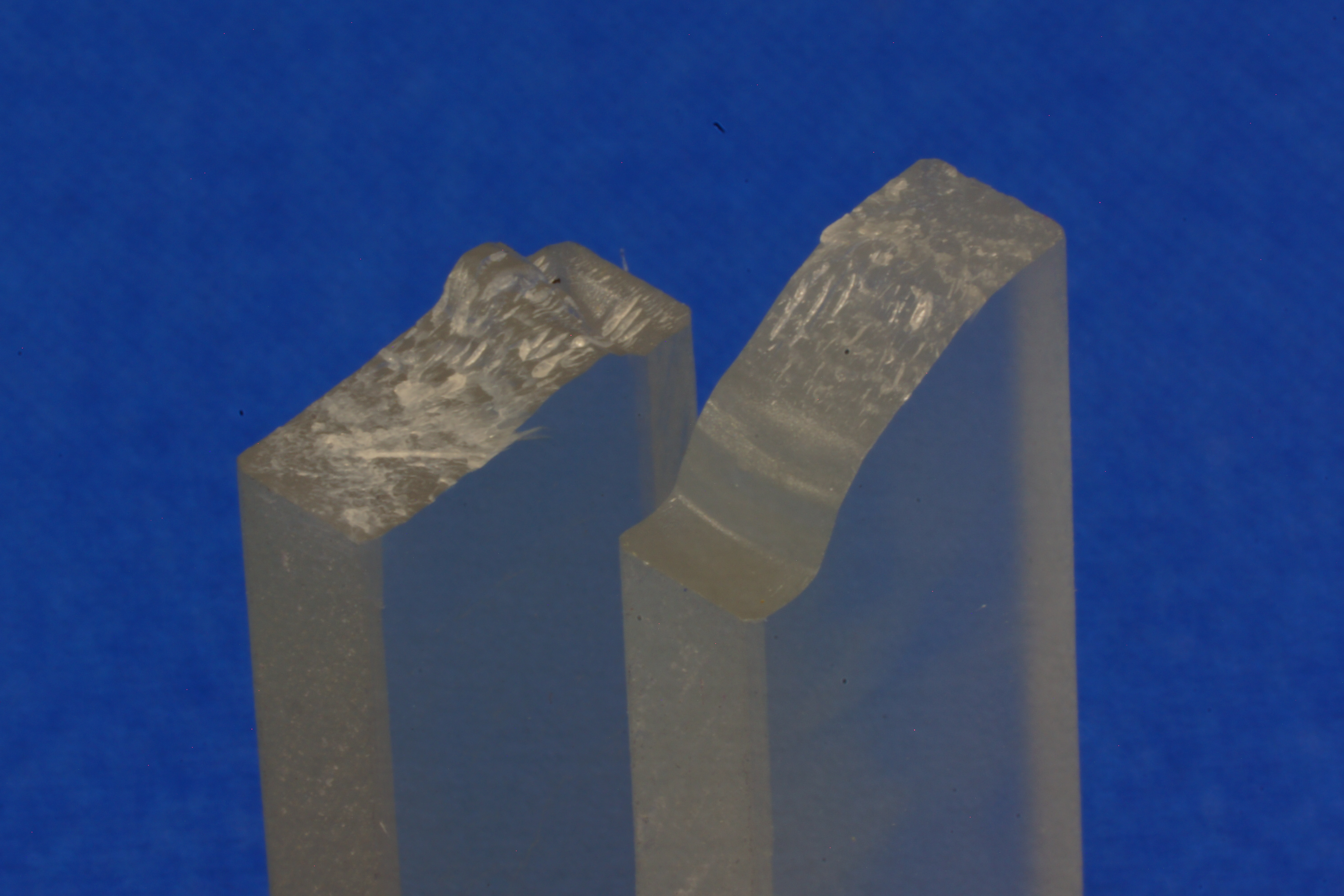

An advantage to reusing wastewater from palm oil is its cost efficiency. Research on agricultural waste using palm kernel shells has been conducted for some time now, but manufacturing costs are high and thus commercialization remains difficult. Raw materials like palm kernel shells, strained lees of sugarcane, grass and trees consist of cellulose, so when converting them to chemicals, they must first undergo the saccharification process which changes them to glucose, a process that can get quite expensive. On the other hand, waste water from palm oil doesn’t require that process, which means costs are kept low.

I think that research and commercialization should be considered separately. While I do perform research to incubate technology for future commercialization on raw materials like palm kernel shells, I actually think that use of palm oil wastewater is appropriate for commercialization at this moment. Additionally, there is a huge amount of juice wasted during the manufacturing process for canned pineapple in Indonesia, so we’re aiming to utilize that waste in the same manner as palm oil wastewater.

Gathering attention from both in Japan and around the world as a hub for biomanufacturing

In 2023, your joint research with Indonesia was selected to the Japan Science and Technology Agency’s “Science and technology research partnership for sustainable development” (SATREPS), which carries out joint research with developing nations to work towards solving global issues.

Ogino:

If we go back in time a bit, Kobe University’s “Innovative BioProduction Kobe” was selected in 2008 as a hub in a project by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). This 10-year project was started with the aim of fusing agriculture and engineering and achieving production of biofuel and chemicals through industry-university collaboration. Through these efforts, Kobe University was recognized as a biomanufacturing hub both within Japan and from overseas, and its research continued to develop and grow.

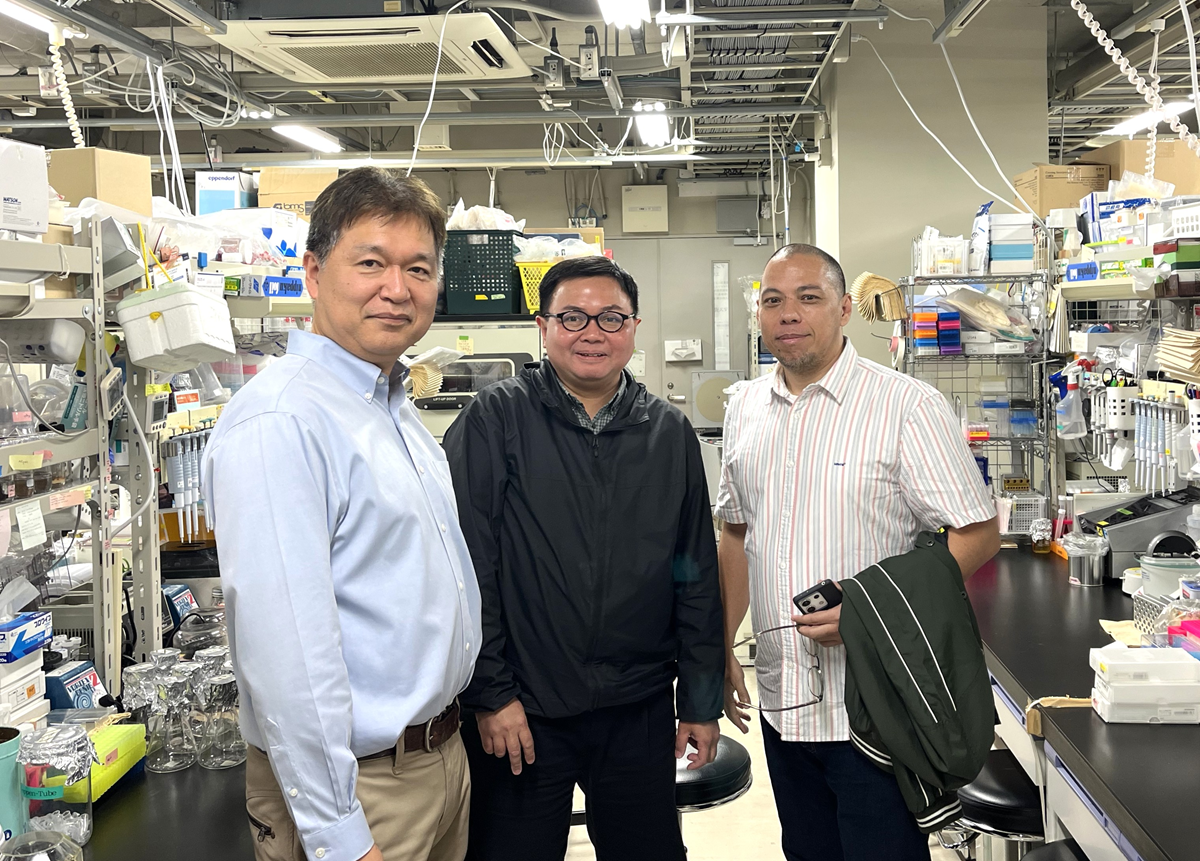

Ogino (left) and his research collaborators, Yopi (right) of the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia and Project Associate Professor Prihardi Kahar (center) of Kobe University. (Photo provided by Ogino)

This joint research with Indonesia was also accepted as a five-year program in SATREPS from 2013, so this project is actually the second time research based on these efforts has been selected. We’ve also received research grants through a variety of additional programs.

Joint research with Indonesia has continued for over 15 years, and just about every year we accept students from Indonesia into our lab. There were even former international students from our lab who were appointed to important positions at universities and government agencies in Indonesia. A huge benefit to this long-standing collaboration is that we have a lot of trusted talent in Indonesia who can conduct joint research in perfect sync with us.

The research that was selected to SATREPS this time plans to produce biofuel and chemicals using palm oil wastewater discharged from food estates, large scale farms that have propagated throughout Indonesia as one of its agricultural policies. We aim to use this biofuel for trucks and tractors on these farms to create a model for a bio-circular economy. We’re also considering having local residents use any leftover biofuel produced.

Solving cost issues, the key to social implementation

How about issues facing social implementation?

Ogino:

Actually, whether or not manufacturing using biomass can progress heavily depends on the price of crude oil. Following the market crash in 2008, the price for crude oil shot up to nearly 150 U.S. dollars per barrel. At the time, it was said that if that price exceeded 150 U.S. dollars per barrel, chemical manufacturing using oil resources simply wouldn’t be economically feasible, which was followed by an increased interest in chemical manufacturing using biomass. However, a subsequent crash in crude oil prices saw that interest temporarily wane. While there are aspects that are affected by external factors, I think we’ve nearly reached a big turning point towards biorefineries.

In Indonesia, there is a regulation that requires the fuel used in things like cars to contain a certain percentage of biofuel originating from palm oil. Currently, however, there is an issue in that this biofuel is created through a chemical process, so I’d like to instead implement the process we’re researching that uses microorganisms. We’ve mostly established this process from a technological standpoint, and our partner company has obtained a patent. Costs are a still an issue, but we’re currently performing preliminary calculations towards the practical application of this process.

The existence of palm farms has been criticized as leading to the destruction of the environment.

Ogino:

I’m of course aware of those criticisms. However, the fact of the matter is that these farms are continuing to expand within Indonesia. Palm cultivation doesn’t require much time or effort, and palm oil is the cheapest and most used vegetable oil in the world.

Half of the products you find in Japanese supermarkets use some kind of palm oil, from things like food, to detergents, to makeup and even coating for paper. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that if we couldn’t use palm oil, life in modern Japan would no longer be viable.

So, if that’s the case, I’d like to use the technology that we developed to ease the burden on the environment, if even a little bit. From the standpoint of someone who has been on site for many years, I feel that Indonesia harbors huge potential to achieve biomanufacturing, so I’d like to continue to develop technology that expands this potential.

Would it be possible to secure raw materials and manufacture biofuel and chemicals entirely within Japan?

Ogino:

We’re exploring procurement of raw materials in Japan as well. In a joint project with Professor SAZUKA Takashi of the Bioscience and Biotechnology Center at Nagoya University, we’re currently performing research on the energy crop sorghum, a type of millet. It’s possible to cultivate it as an energy crop since it grows quickly and doesn’t compete with the crops used for food. The crop is currently undergoing selective breeding at Nagoya University, and eventually, we aim to use it for sustainable aviation fuel.

It’s also possible to make use of sugar beets, a raw material used to make sugar. Currently, demand for sugar is on the downturn in Japan due to health consciousness. I want to create a movement which shifts production of these plants to be used as fuel; in fact, we’ve already begun research in collaboration with sugar manufacturers.

Lately, sustainable aviation fuel has been gathering attention, has it not? This is due to the EU requiring the aviation industry to use a certain percentage of sustainable aviation fuel, which in turn has seen airlines from all over the world begin to adopt it. It’s even possible that in the future, competition for raw materials will happen all over the world, so securing raw materials and developing technology in Japan will become extremely important.

When advancing biomanufacturing, even if the technology is the same, there is a need to prioritize raw materials and culture that are appropriate for the country and its land. When aiming to establish a bio-circular economy, that perspective becomes very important. Thus, in our research, we also collaborate with researchers in the social sciences to consider the modification of people’s behavior, or put simply, how to push their “motivation button.”

Pouring energy into international students from around the world and nurturing talent

What are your goals moving forward?

Ogino:

Kobe University is a hub for biomass research in Japan, so we’ve received many international students from around the world. In addition to Indonesia, there are students from Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Brazil and many other countries. We’ve also already begun conducting joint research with Thailand and Malaysia in addition to our research with Indonesia, and I’d like to further fortify our collaborations with countries rich in biomass. Of course, we’re nurturing Japanese students as well. Nurturing the talent that will bear the future is so important.

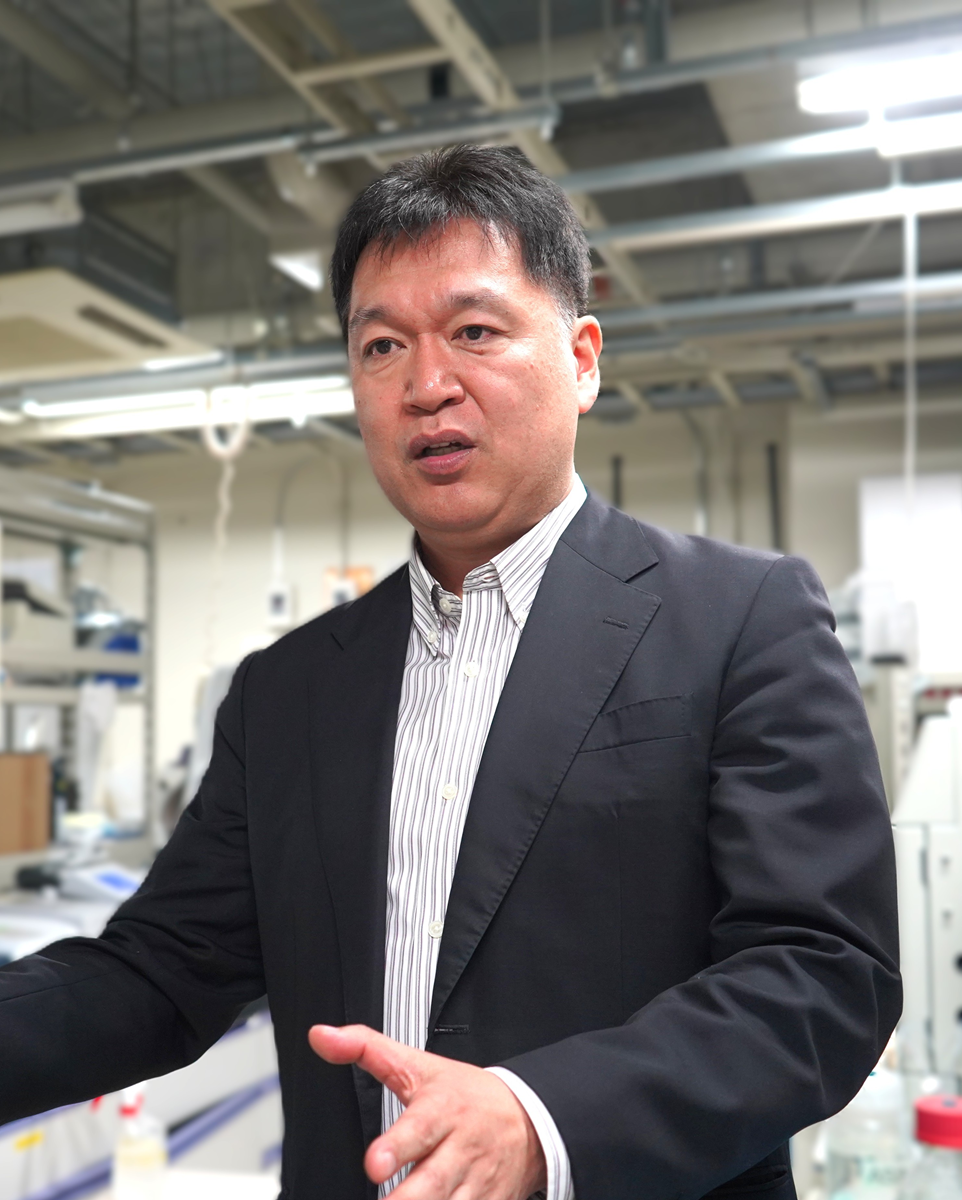

Ogino speaks about research with students and a researcher

In addition, from April 2025, I’ve also been working as representative director of the Organization for Engineering Biology, which promotes infrastructure development of cutting-edge bioengineering through industry-government-university collaboration. Over 30 corporations involved in biomanufacturing have joined this organization, and I’d like to continue realistic discussions about manufacturing from biomass with these corporations.

As a short-term goal, we’re thinking of starting our own company this year, if possible. I think it might be realistic to first establish a venture business in Japan and have a branch office in Indonesia. As someone who has built connections with people and organizations in both countries for many years, I feel as though it’s my role to tie together corporate partners in Indonesia with businesses in Japan. From this year on, I’d like to accelerate developments toward practical applications.

Resume

In 1995, graduated from the Department of Chemical Science and Engineering of Kobe University’s Faculty of Engineering. In 1997, finished the master’s program at the Department of Chemical Science and Engineering of Kobe University’s Graduate School of Natural Sciences. In 1999, became assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering of Kanazawa University’s Faculty of Engineering. In 2002, became assistant professor in the Division of Global Environmental Science and Engineering at Kanazawa University’s Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology. In the same year, received his doctoral in engineering from Kobe University. In 2007, became associate professor at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Engineering. In 2016, became professor at the same graduate school. Has served as unit head of the Advanced Analysis, Evaluation and Processing Research Unit at Kobe University’s Engineering Biology Research Center since 2018 and as representative director of the Organization for Engineering Biology since April 2025.