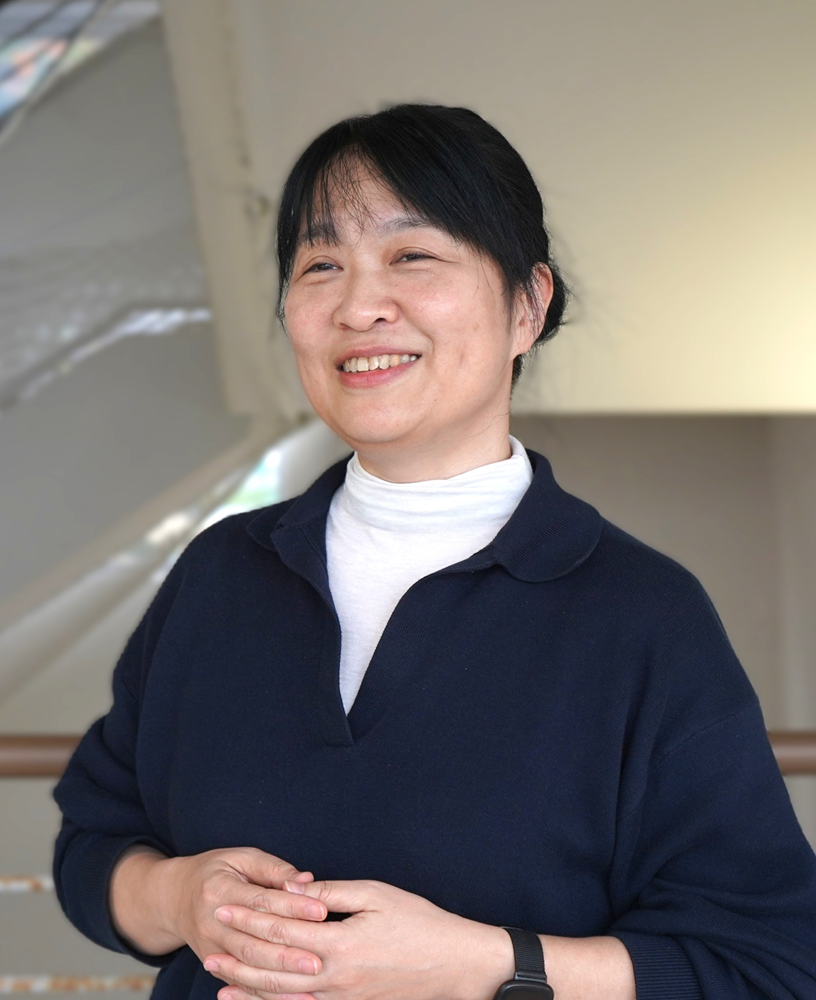

How do people perceive the risks of chemical substances in their everyday lives? Associate Professor MURAYAMA Rumiko of the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, an expert in environmental health, performs research on that very topic. Her research covers everything from risk perception to the role of communication, while also focusing on how awareness shifts with the changing times. The content of her research is thought-provoking even in understanding the risks associated with things that don’t involve chemical substances. She told us about the nature of risk perception in humans that she has uncovered through her research.

Humans don’t assess risks based on scientific facts

Generally, how do humans perceive risks?

Murayama:

People don’t assess risks based solely on scientific facts or objective values. We need to understand that humans have certain quirks in how they think.

When we assess risks, we think about whether something is scary or not, as well as whether it’s new or unfamiliar to us. Also, we tend to underestimate risks for things that are profitable to us or things that we do spontaneously.

Our greatest risk is losing our lives. But people don’t evaluate their decisions based on that alone.

For instance, when it comes to the risks involved with automobiles, between 2,500 and 3,000 people lose their lives in traffic accidents in Japan each year. However, according to our research, only about 30% of people consider automobiles to be “unsafe.” On the other hand, the percentage of people who think food additives are “unsafe” jumps to around 60%, far more than that of automobiles. People have this perception despite these additives meeting food safety standards.

Rather than data on the number of deaths, it’s the fear within us that leads to such assessments. This means that the risks that people perceive aren’t equivalent to actual risks.

It is true that chemical substances like food additives are somewhat scary.

Murayama:

There’s even a word for fear and distrust of chemical substances: chemophobia. I think that chemical substances are generally met with quite a bit of fear and distaste.

However, elements and elemental compounds are, generally speaking, all chemical substances. There are many that exist in the natural world, even down to the iron (Fe) in our blood and salt (NaCl). Of course, the detergents and plastics we commonly use are also chemical substances.

There are over 279 million entries in chemical substance databases around the world, with around 70,000 of those said to be used for engineering in Japan. New substances are being discovered all the time.

While there are substances with the potential to cause harm to people if used incorrectly, there are also those that are used to create all kinds of useful things for us, making it difficult to live completely free from these substances. What we need to do is manage the risks associated with these substances.

When it comes to discussions regarding chemical substances, the importance of risk communication among related parties, including citizens, is often indicated, but simply providing a one-sided scientific explanation won’t do. Like I mentioned earlier, people don’t evaluate risks solely based on science, and more often than not they dislike chemical substances.

If you consider the issues associated with chemical substances as issues associated with human health and livelihoods, then you must first clarify how people perceive the risks of these substances and search for the best way to communicate with them about those risks. We need to think about how to manage chemical substances only after sufficient communication has taken place.

Wanting to think about the structural issues behind divisions

What led you to begin your work on risk perception?

Murayama:

While I was working at the Institute of Public Health (now the National Institute of Public Health), air quality standards were established for a substance called benzene, and my involvement in that led to my current work on risk perception. We began by surveying whether the standards established for benzene matched with how the general public felt, and from there, we expanded our research to other substances. We also investigated citizens’ awareness regarding radioactive materials in Fukushima Prefecture following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.

Through our surveys in Fukushima Prefecture, I felt even more strongly that the issues involved with the risks of chemical substances are issues that affect people and their livelihoods. The municipality where we performed our interview surveys didn’t receive an evacuation order; rather, there were people who voluntarily evacuated, people who stayed and people who evacuated temporarily and then returned to the area. There are many instances in which ways of thinking differ between age groups, but even those of similar age can think quite differently. Even among those raising children, there were some who were quite worried about the effects of radioactive materials, while others claimed that there was “no use thinking about it.”

Risk perception differs from person to person, which created a situation in which people didn’t talk about radioactive materials with those of differing opinions so as not to hurt each other. As a result, an invisible rift gradually began to form among the people of the area.

Recently, we’ve seen divisions among people regarding their thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine as well.

Murayama:

With the emergence of social media, it’s become quite easy to express our opinions to the world and find other people who share those opinions. I’m sure that’s a factor behind these divisions.

There have always been agreements and differences of opinion on things like nuclear power plants and protests about food additives, but we’ve never been able to connect with those who agree with us quite as much as we are now. And it’s not limited to issues related to vaccines: differences in opinion on a certain incident form a starting point which spreads to opinions on other things, and now I feel as though we’re forming these clusters of like-minded individuals.

I think that, just by its nature, risk perception leads to these kinds of divisions. It’s not a problem to find something scary or unpleasant. Like I touched on at the beginning, it’s fine for people to have their “quirks.” But if these divisions lead to identity politics (movements from groups that demand policies and politics for their own benefit based on a specific identity) or deepen rifts between the people themselves, then we need to think about the structure of these divisions.

Communicating risks not as persuasion, but as a mutual exchange of opinions

What is the role of scientists in risk communication?

Murayama:

I think we should think about the overall picture that includes all stakeholders, not just scientists. Specialists and risk managers can also see things as a citizen. Moreover, citizens aren’t “people who don’t know anything”; in fact, there are times when citizens have high levels of expertise in a variety of fields.

In this day and age, it’s clear that the kind of communication in which experts and risk management officers simply explain and persuade just doesn’t work, and I think the number of experts who still use that outdated approach is also on the decline.

What’s important is the mutual exchange of opinions among those involved. It’s creating a relationship in which everyone can share information and concerns and be honest when there’s something they don’t understand. Moreover, it’s crucial to have this type of exchange all the time, not just after incidents.

Following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, discussions took place between a local government employee and residents in the area regarding temporary storage areas for things like contaminated soil. Of course, a resolution wasn’t going to be reached simply by providing citizens with scientific data. As talks were failing, the government employee devised all sorts of ways to deliver information to residents, such as explaining the characteristics of radioactive materials, all the while providing hundreds of opportunities to exchange opinions.

That’s not to say that the residents were completely convinced. But this did form a relationship in which they could go and talk with the government employee when there was an issue. They didn’t necessarily like the employee, but there was a certain level of trust there. This showed me the importance of such a relationship.

But in the case of Fukushima, building that post-crisis relationship began from a negative place. Ideally, it’s important to build that relationship of trust all the time. From there, various related parties like citizens, government officials, corporations, scholars and the media need to enter discussions on equal footing.

What kind of research would you like to conduct moving forward?

Murayama:

About 40 years ago, American psychologist Paul Slovic presented a famous theory which stated that risk perception consists of two factors: “dread risk” and “unknown risk.” But times have changed, and I feel as though those factors have gone through some changes as well.

The development of information technology has allowed us to see clear images of even the deepest reaches of space. We can immediately acquire scientific information in a wide variety of fields over the internet. 40 years ago, things that we scientifically didn’t know might have been classified as “unknown risk,” but nowadays, I think those have shifted to “dread risk.” Compared with the past, many more things have become visible to us, so I think the ways in which humans fear have also changed.

We need to consider approaches to risk perception and communication with an understanding of such changes. Kobe University has an atmosphere that promotes co-creative, interdisciplinary research, so I hope to work together with researchers in a variety of fields, like philosophy and mathematics, to pursue brand new research topics.

Resume

In 1995, completed the master’s program at the Graduate School of Human Sciences, Waseda University. In the same year, became researcher at The Institute of Public Health (now the National Institute of Public Health). In 2002, became assistant professor at the Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University. In 2007, acquired her doctoral degree in medicine from Juntendo University. In 2013, became associate professor at the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University.