The university is a place of research and knowledge. But have these things actually served to make people happy? Professor ISHIDA Tatsuro asked himself this question time and time again during his two-year-plus tenure as deputy director of Kobe University’s Office for Promoting Well-being. While performing research and diagnosing and treating patients as a physician, he also pondered their well-being. In addition, as part of a team effort to contribute to society with municipalities in Hyogo Prefecture, Ishida volunteers to provide medical care to the community. We asked Ishida, who currently serves as dean of the Graduate School of Health Sciences and who concurrently served as director of the Center for Advancement of Community Medicine through March 2025, about the current state and future outlook of well-being promotion at Kobe University, as well as his perspectives on research and medical settings.

What can universities do about the low happiness levels in Japan?

You’ve been involved in the Office for Promoting Well-being, but how do you feel about “well-being” itself? Have people become happy?

Ishida:

University faculty, whether they’re in a department that specializes in medicine or otherwise, perform research because they want to be useful to the world, to society and to the people in it or because they want to directly contribute to society. But if you actually ask people whether they’re happy or not, for whatever reason, data shows that happiness indicators and perceived fairness among the Japanese is low. Even now, Japan remains the fourth most powerful economy in the world, with high levels of education and well-developed social security systems such as health insurance and pension, but despite that, the happiness levels of its citizens are even lower than countries overseas that don’t have these systems.

But why is this? Is the research that we conduct at the university really for the people? What do we the Japanese people want, and where are we headed? These questions formed the basis for discussions at the Office for Promoting Well-being.

While of course it’s important for university faculty members to produce outstanding academic publications and make outstanding discoveries, I feel as though Kobe University, which conducts education and research in the city of Kobe itself, has to become a university that is needed by the community. To that end, it’s crucial to implement and utilize the knowledge, research results and activity accumulated at Kobe University in society while revitalizing the community. I think that the establishment of the Office for Promoting Well-being and the Advanced Research Center for Well-being provide an opportunity to reset and reexamine the activity of each laboratory and each faculty member to promote research, activity and education that brings the entire university together under the keyword of “well-being.”

Treatment catered to each patient, not just a generalized response

What are your thoughts on well-being in medical treatment, your area of expertise?

Ishida:

As a physician, I’ve always had saving lives, treating illnesses and extending the average lifespan on my mind, but now I ask myself whether or not those are truly the goal when it comes to human happiness. For instance, you can have a successful surgery or treatment, but if that patient never gets better and goes on living their life in discomfort, then that raises the issue of the difference between that and a “healthy lifespan.” Over the years, medical treatment has been thought of more as needing to be catered to each patient, and we’ve seen shifts in that direction. You can’t have this biased idea of professional self-righteousness that says that illnesses should be treated in specific branches of medicine. We as a university have to disseminate and recommend the type of research that leads to medical treatment that truly understands the daily lives of patients to relieve their emotional and physical pain and eliminate their discomfort.

The best condition for people is to be illness-free. To achieve that condition, first of all, prevention is crucial. In the end, extending healthy lifespans through thorough prevention is the goal. However, prevention comes in many forms and with many differing ways of thinking, so what is necessary for prevention changes depending on the person. I specialize in the circulatory system. So, for instance, some 10 years ago we told everyone to not get fat, to not eat greasy food, and to eat more fish than meat since obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes and high blood pressure are all bad.

But now, our society has gotten even older, and there are many elderly individuals who have lost both weight and physical strength. We’re currently seeing many individuals who are considered frail, in which the mind and body become less active due to aging, as well as patients with sarcopenia, in which muscle mass is lost due to factors which also include aging. In order to prevent bone fractures, dementia and infectious diseases in the elderly, we need to improve nutrition to raise physical strength and immune levels. This requires guidance tailored to each individual, something that differs from obesity prevention for young people. In other words, this is an era that requires detailed guidance that is right for each person, not something that’s been generalized. Universities elucidate specific methods for that kind of personalized guidance and verify their effects, something that is crucial for extending healthy lifespans.

This idea came about after reflecting upon generalized guidance for the entire Japanese population based on the average sodium and cholesterol intake values of its citizens. Rather than just raising and lowering the average values of the population as a whole, we must think of prevention for each individual and the state of their health. Providing detailed measures for each individual to achieve and maintain health is what well-being is all about.

Local production and consumption of medical resources and a 30% increase in medical school enrollment

You are personally working to contribute to the community through an activity known as “Project ‘Let’s go to medical school.’” What kind of activity is that?

Ishida:

In our modern society, the collapse of regional medical care has become a serious issue due to shortages and uneven distribution of doctors. We’ve tried many countermeasures, but not only has the issue not been resolved, it’s actually getting even worse. I’m involved in a physician development system promoted by Hyogo Prefecture called the “regional quota system.” This system sees young physicians from urban areas receive scholarships on the condition that they spend a few years at a rural hospital following their graduation. However, once this period ends, their loans are then waived, so many use that opportunity to leave these rural areas, leaving the issue of doctor shortage fundamentally unresolved.

That being the case, it would be ideal if individuals from these rural areas became physicians and health workers at the hospitals located there. Since they’ll continue living in the area, this also serves to counter population decline and contribute to the community’s development. However, since currently many students who enter medical school come from preparatory schools in urban areas, entering medical school remains a significant hurdle for students from rural public high schools.

Since 2019, I’ve worked with the Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education to carry out a program for nurturing medical talent from high school students in medically underserved areas within Hyogo Prefecture. This doesn’t just involve physicians either; we’ve expanded the program to include medical staff such as nurses and therapists as well. This activity is called “Project ‘Let’s go to medical school,’” and is now being carried out in the three cities of Toyooka, Sumoto and Sanda to produce medical professionals from the area, working for the area.

Specifically, we hold on-site lectures and debates on medical issues (such as euthanasia) at high schools. We also have high school students interested in the School of Medicine visit the university to experience things like measuring insulin and performing ultrasounds to cultivate their interest in medicine.

In the three years since the start of the project, Toyooka High School and Sumoto High School have seen a 30% increase in students entering medical schools. We’re starting to see the results of this project as the first student participants are now beginning to return to work at local hospitals. I think this has directly led to countermeasures for population decline and regional revitalization using medical professionals as a model.

In Toyooka City, Toyooka Hospital has taken the initiative to create a scholarship for local students who enter medical school while holding seminars to encourage them to work at hospitals in the area. Moving forward, it’s important to foster this situation and work as a region to follow up with students who went to medical school. I’d like to create a virtuous cycle that maintains this medical school enrollment rate and has students from the area become medical workers at local hospitals five or ten years from now.

Healthy aging — That’s our happiness

Please tell us about your current research topic.

Ishida:

I specialize in the circulatory system and my ultimate topic of research is “healthy aging.” In our lab, we discover new circulatory diseases and develop new methods for treatment and diagnosis.

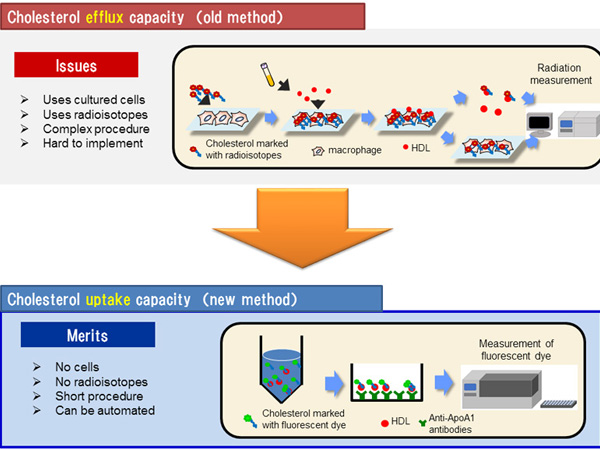

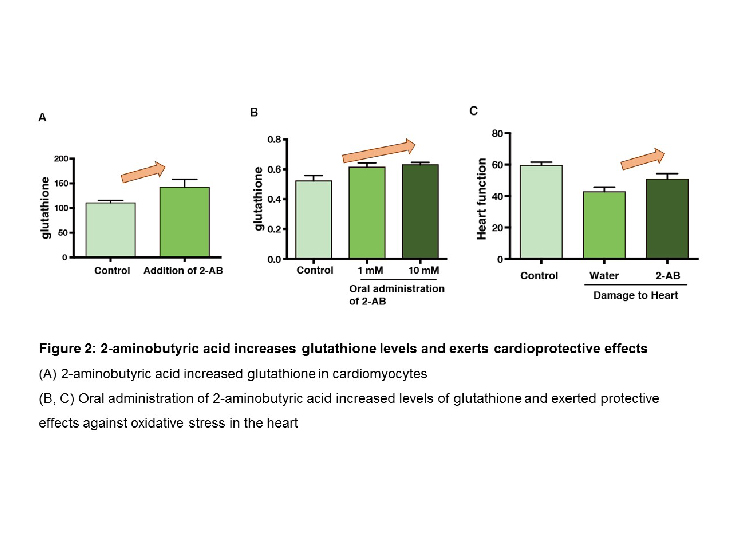

For instance, good cholesterol, or HDL cholesterol, is something that can be measured in the blood. However, if your HDL cholesterol is high, that could mean that you’ve got a lot of it, or that it’s of high quality. Currently, we’re developing a method of expressing HDL cholesterol quality jointly with medical corporations. We’re also conducting research on medicines and lifestyle habits that affect HDL cholesterol quality. If we’re able to easily measure HDL via automation, we’ll be able to understand the effects of things like tobacco, exercise and medicine on the amount and quality of HDL cholesterol. Additionally, we’ll be able to elucidate long term effects of high-quality HDL cholesterol, such as resistance to hardened arteries. My assumption is that they’ll make use of these applications in medical settings.

Also, at the Hyogo Prefectural Awaji Medical Center, we’re performing joint research that involves surveying the status of patients with chronic heart failure. Since not many of the locals venture off the island, we’re able to track individual patients following their treatment and follow up with them. Started around 2020, this longitudinal study will last for ten years. Using blood samples from patients, we can measure fat data and HDL cholesterol in the blood to track their heart failure and affected lifestyle habits. We’re looking to elucidate the factors that affect heart failure across the entire island and provide that data as feedback to residents to prevent the occurrence and reoccurrence of heart failure as well as make use of the data for rehabilitation. I’d like to disseminate what we find through this research not only to Awaji, but to many regions to increase the number of healthy individuals in society as a whole.

Nurturing a mind for happiness at the new graduate school

What are your future prospects at the Office for Promoting Well-being?

Ishida:

The role of the Office for Promoting Well-being is not just to support research at the Advanced Research Center for Well-being; we also need to enhance education and regional contribution. On the education side, from academic year 2024, we’ve begun an educational program in well-being at the Graduate School of Health Sciences. We’ll increase the number of subjects from the academic year 2026, and we’re also considering allowing students from other graduate schools to take courses in the program, primarily those in the Graduate School of Health Sciences and the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment. We’re also looking to further enhance the Regional Partnerships Division to reinvigorate connections with the society of the region. On top of that, we’re also putting energy into collaborations and joint research with non-government corporations and administrative agencies. I’d like to put our energy into bridging the research results produced by the Advanced Research Center for Well-being and applications in regional society. As this is a university-wide project, now marks a crucial moment for us to be able to produce significant results.

In the two years of this activity, has awareness within the university changed?

Ishida:

When the Office for Promoting Well-being was established two years ago, even faculty at the university reacted with “What is well-being?” However, as the world gradually changed and well-being began being frequently picked up by the media, it began to permeate into corporations as well. These social changes helped to create an atmosphere among faculty members that well-being is important and now I feel as though that perception has spread throughout the university.

But I feel that an issue in carrying out studies on well-being is that Kobe University’s campuses are currently scattered all over the place. Kobe University has many outstanding, motivated researchers. I’ve also seen cases in which these researchers carry out research in very similar fields at their respective graduate schools. In order for the Office for Promoting Well-being and the Advanced Research Center for Well-being to serve as a bridge between these geographically separated researchers, we’ve held many meet-and-greets over these two years. It will take some time before we actually see some results, but I would like to continue to promote multidisciplinary co-creation and produce these results at an accelerated pace.

From the academic year 2026, Kobe University will merge its Graduate School of Health Sciences into the Graduate School of Medicine. I would like to permeate this graduate school with ideas about public health and nurture a mind for well-being among its students and faculty. I want to organically link these currently separate graduate schools, whose work was already related to well-being, and bring the awareness of students and faculty closer to the perspective of well-being. I’m looking to not simply cure illnesses but also make patients happy and contribute to society. To that end, faculty members involved in medicine, health sciences and nursing care must come together and change their awareness to one in which they will continue to think about and discuss medicine and medical treatment from the perspective of well-being. By contributing those results back to society, I hope to fulfill my dream of making Kobe University into a university that is needed by the region.

Resume

In March 1990, graduated from Kobe University’s School of Medicine. In 1998, completed the doctoral program at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Medicine and received his doctorate in medicine. In June 1999, became a researcher at Stanford University’s School of Medicine. In July 2002, became a medical researcher at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Medicine. In July 2005, became a research associate and in April 2007, became an assistant professor at the same graduate school. In August 2009, became an associate professor at Kobe University Hospital and in April 2014, became a project professor at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Medicine. In April 2022, became a professor at Kobe University’s Graduate School of Health Sciences and in April 2025, became dean of the same graduate school.