When people present themselves as capable or humble, the way this influences other people’s evaluations of one’s true ability and character depends on one’s usual performance. Kobe University and University of Sussex researchers thus add an important factor in our understanding of how the relationship between self-presentation and perception develops with age.

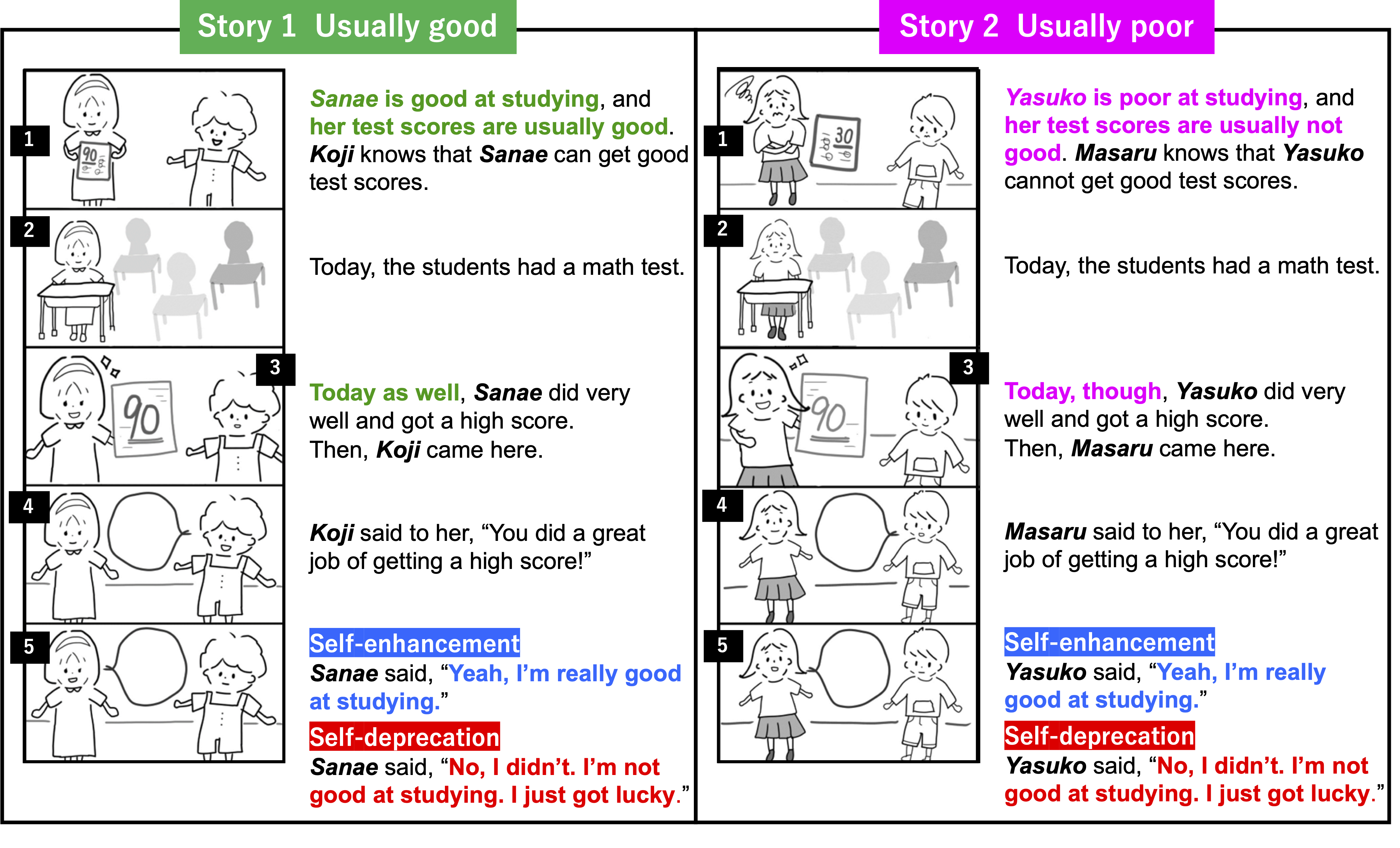

When being praised, people may respond with self-enhancing or self-deprecating statements to manipulate how others perceive them. Kobe University and University of Sussex researchers presented elementary school children and adults with four different scenarios and asked them how the other person would evaluate the protagonist’s ability and character, to find out how the evaluation of self-presentation develops as children grow up. This figure is one example of two scenarios in which the protagonist is a girl and the other person is a boy. For the other two scenarios, the genders were switched. © HAYASHI Hajimu (CC BY)

People want to be liked. Amongst the many ways of achieving this, making statements about oneself to manipulate other people’s evaluation is called “self-presentation.” Both the ability to do so and the effect this has on others’ evaluation of one’s ability and character develop as children grow and have increasingly complex understandings of others’ minds. A standard way of measuring these evaluations is by presenting children of different age, and adults, with a story in which a protagonist receives praise for an achievement and in response self-deprecates or self-enhances. Study participants are then asked to rate how other people might evaluate the protagonist’s ability and, separately, their character. However, what these studies have not considered is that for such an evaluation, people actually also consider whether the protagonist receiving praise usually performs well or not. This is because a self-deprecating statement by a usually poorly performing protagonist should be perceived as honest and nice, but the same statement by a usually well performing protagonist might be perceived as false modesty. Furthermore, a self-enhancing statement by a usually poorly performing protagonist should be perceived as blatant falsehood and very awkward, and the same statement by a usually well performing protagonist may also be perceived as awkward and boastful.

A study by Kobe University developmental psychologist Hajimu Hayashi and University of Sussex developmental psychologist Robin Banerjee closed this gap by presenting Japanese elementary school children in second grades (7- and 8-year-olds) and fifth grades (10- and 11-year-olds) and Japanese adults with a more complex scenario. Hayashi explains, “In studies with children, the tasks are usually simplified as much as possible and scenario characters often don’t have a history. However, in our daily interactions with others and making social evaluations and judgments about them, we consider their past or usual performance or behavior, and I wanted to investigate whether the same might be true for self-presentation.” Study participants were introduced to a protagonist and another person and were told that that other person knows the protagonist’s usual performance (i.e., usually good or usually poor) in a given task. In the story, the protagonist then performs that task well and receives praise from the other person and responds in either a self-deprecating or self-enhancing way. The researchers first asked the study participants a few test questions to confirm whether they understood the scenario, and then asked them to rate how the other person evaluated the protagonist’s ability and character.

In the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, the Kobe University and University of Sussex team have now published their results. They showed that in adults, assumed to have a fully developed theory of mind (the ability to attribute to other people thoughts and emotions different from one’s own), false statements by the protagonists were evaluated more negatively. This pattern of more negative evaluations of a usually poorly performing, self-enhancing protagonist’s character was also observed in fifth graders, but it was less evident in second graders. Thus, by around the age of 10 years, the tendency of self-enhancement to lead to more positive ability evaluations of usually poorly performing protagonists disappeared and self-enhancement led to less positive character evaluations. These findings imply that the evaluation of self-enhancement and self-deprecation develops substantially from around the age of 7 to 10 years. Furthermore, second graders overall evaluated self-presenters as more competent and nicer.

While this already portrays a clearer picture of how we evaluate self-presentation, the developmental psychologists caution that their data still cannot capture all relevant factors. For one, irrespective of their usual performance, protagonists invariably did well in the instance before receiving praise. But self-presentation also occurs around performing poorly, and the perception of such statements might be interpreted differently depending on the protagonists’ current performance. And indeed, there were no negative evaluations of protagonists’ character, just more or less positive ones, and at worst only barely negative evaluations of protagonists’ true ability. A similar complexity arises around the question of whether the current performance was due to intrinsic talent or effort. In addition, the cultural setting of the study, which was conducted with only Japanese participants, needs to be considered.

The researchers say that their work has implications for how we evaluate children’s statements when they self-present and how we help them navigate issues arising from interpreting others’ statements. The better we understand the development of how we interpret others and which abilities we may expect at what age, the better we will be able to provide that guidance. Hayashi says, “I realized once again that the speech comprehension and communication of children in the early elementary school years are different from those of adults. We believe that if adults are aware of these differences, they will be able to provide children with deeper instruction and guidance.”

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant JP19KK0309). It was conducted in collaboration with a researcher from the University of Sussex.

Original publication

H. Hayashi et al.: Children’s and adults’ evaluations of self-enhancement and self-deprecation depend on the usual performance of the self-presenter. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jecp.2024.105886

Release on EurekAlert!

Modesty and boastfulness – perception depends on usual performance