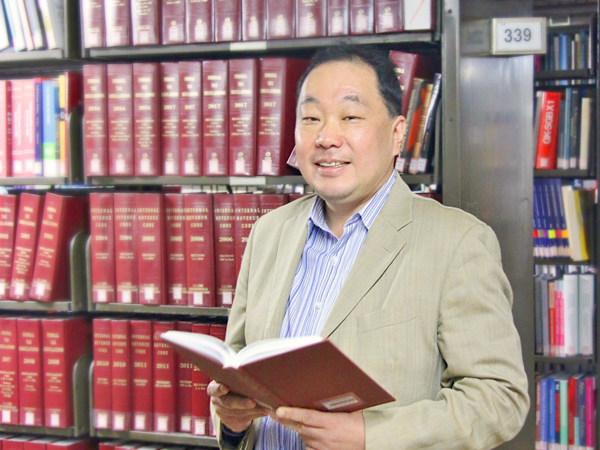

Professor Emeritus IOKIBE Makoto was an influential scholar at Kobe University and preeminent expert on Japanese diplomacy, US-Japan relations and the postwar US occupation policy of Japan. He also served as advisor to the government on post-disaster reconstruction efforts and as the president of the National Defense Academy. What enables a person to become a leader in so many fields? And how did his personal experience influence his research and work? We asked one of his former graduate students, Professor MINOHARA Tosh at the Graduate School of Law and Politics at Kobe University, who, like his mentor, also specializes in US-Japan relations.

“It is crucial that people do not take for granted the importance of US-Japan relations.” This was Iokibe’s strong conviction, a former professor of Japanese political history at Kobe University who instilled in all those that he taught the realization that both in past and present, the United States was the bedrock to the stability and security of Japan. His former graduate student and academic successor Minohara, a Japanese American, explains: “This doesn’t mean that he was totally enamored with America; he saw it for what it was, both the positive and negative. But he also was aware that never before in our history had a victor been so generous to the vanquished. Even with the Cold War looming, what America did for Japan went well beyond the pursuit of national interests. The United States not only helped Japan back on its feet economically, it also helped to reestablish a stable democracy. Professor Iokibe, as a pragmatic realist, was grateful for this, and he wanted to ensure that the future generation of Japanese will never forget this.”

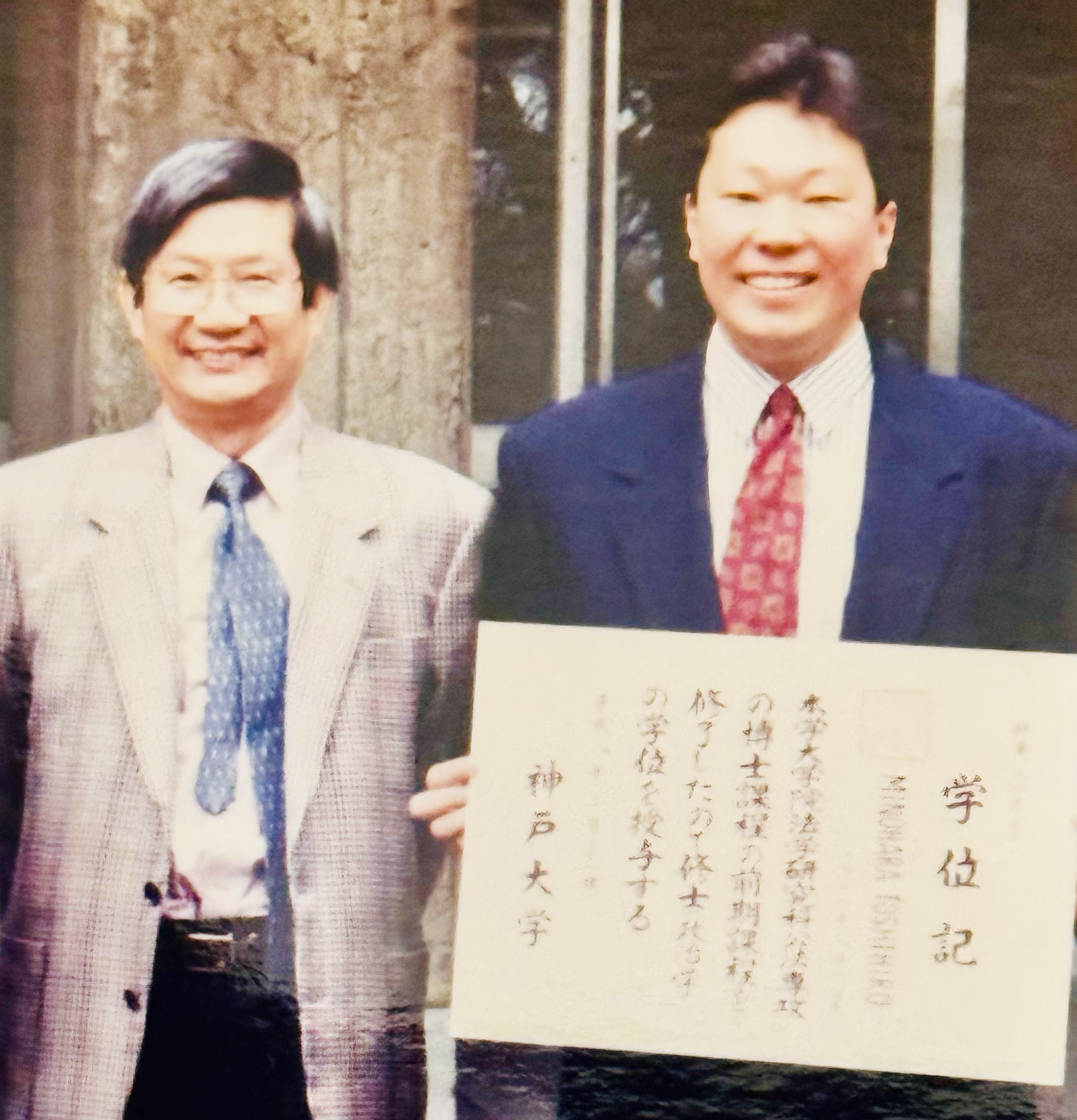

But Iokibe was definitely not a preacher. His objective as a scholar was to nurture the next generation of scholars in his field. The epitome of this was his seminar, where he would freely and openly discuss with students not only the classics, but also current global events for hours on end. “He really loved his students. I really felt that we were his family outside his home. And we just savored every moment with him,” says Minohara, who has many stories to share of how much his mentor liked to talk, sometimes extending way into the next class period. But the students didn’t mind at all, as they intently absorbed every word he would say. Minohara recalls a time that Iokibe began to shed tears as he explained how the Japanese ambassador in Moscow desperately sought to convince his government to the end the war prior to the atomic bombings. “Such empathy comes from the fact that he was a very warm person. And being a professor myself now, I too enjoy the time with my seminar students. These are the moments in which I become cognizant of the fact that I’m directly touching the lives of a future generation. I encourage them to become free and independent thinkers as well as problem solvers. I also try to instill in them the idea that they are vital stakeholders of this world, and through their actions, they can really make a difference. This is what makes me content that I took up this profession.” It was, of course, Iokibe who guided Minohara on the path of becoming an academic, saying: “If making lots of money is what’s important for you, then you should attend law school in America. However, if you want to pursue a truly noble dream, then you should remain here to become a scholar.”

In 2006, Iokibe retired from Kobe University where he had taught since 1981 to become the 8th president of the National Defense Academy. Back then, the academy was still very much science oriented, but his presidency helped to increase the prestige of their social science and humanity majors. Minohara explains: “He instilled the belief that history is relevant. He looked at the various processes at play surrounding the key decision makers and the impact that they had. But more than that, he made the real human being emerge from the decision maker. Iokibe just didn’t explain the historical facts, he would also show what made them tick and what worries and doubts they possessed as they made key decisions that would determine the fate of the nation. He also would also explain the rationality of their decisions as well the ramifications. Furthermore, he would connect the past to the present so that we could understand its relevance to the world we live in today. History may not repeat itself, but it definitely rhymes, and it is perhaps the only tool that can shine some light onto the direction that we are heading. I think, deep down, Iokibe also shared this view.”

But Iokibe was a scholar who would not be confined to his office. He saw it as his duty to constantly interact with society, and even as the president of the National Defense Academy where he was known to have shared his wisdom with many, from prime ministers to cadets. One change that he implemented at the academy was that the cadets, as members of the local community, had to actively assist in times natural disasters and not be mere bystanders.

Jumping back in time to 1995, a large earthquake struck Kobe on January 17, now known as the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake. It was the first major earthquake to hit Japan in several decades and both the local and national government were ill-prepared to deal with a disaster of this magnitude. “People in Kobe were initially pretty much left to their own resources. I later learned that some Japan self-defense forces (JSDF) actually were mobilized to provide assistance, but they were later reprimanded because they broke the chain of command and acted without orders,” recalls Minohara.

Iokibe experienced the earthquake first-hand in his home. He lost a seminar student in the disaster, and this became a turning point. Minohara explains: “A major pillar of his research was on American occupation policy of demilitarizing and rebuilding Japan. He realized the vital importance of policy makers during a national crisis, and in his mind, even considering the difference of magnitude, a post-major earthquake was in many ways very similar to an aftermath of a war. Both required massive and meticulous planning to allow for rebuilding that will allow the city or nation to rise from the ashes.” As a prominent advisor to the government on foreign policy affairs, he adroitly used his influence to push the government into action. But much more than just immediate assistance was on his mind. “For example, the Port of Kobe was devasted by the earthquake and during the time it was unable to function, Busan and other Asian ports surpassed it in terms of cargo volume passing through it. Iokibe suggested to the government that, when rebuilding, the port should be made bigger, better, and more efficient to take back the lead from the rival ports.” However, at that time, the government rejected this on grounds that Kobe shouldn’t benefit from the disaster and that returning infrastructure to its original state would suffice.

But times have changed. After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, and the recent 2024 Noto Peninsula Earthquake, the government as well as the JSDF sped into action without delay and played a proactive role in helping those in need. “A significant portion of this was due to Iokibe’s contribution,” Minohara says about his mentor, who later chaired the Reconstruction Agency Committee to advise the government on post-disaster rebuilding efforts in 2012. Four years later, he would again serve on the expert panel for reconstruction after the Kumamoto Earthquake.

What binds everything together? And what enables a single person to be of national influence on so many different fields? Minohara says: “Iokibe truly valued, at the very basic level, the human being (‘hito’ in Japanese). And that’s also why I believe he was such warm person; he placed tremendous value on humanity. One thing he clearly instilled in people was the idea that ‘People make history, and history makes people.’ Maybe it was this conviction that made it imperative for him to remind all those around him that they have a role to play by giving back to society. And that’s exactly what I’m doing through my nonprofit organization, Research Institute for Indo-Pacific Affairs (RIIPA). This is my small way of contributing to society as well as to honor the memory of my mentor.”