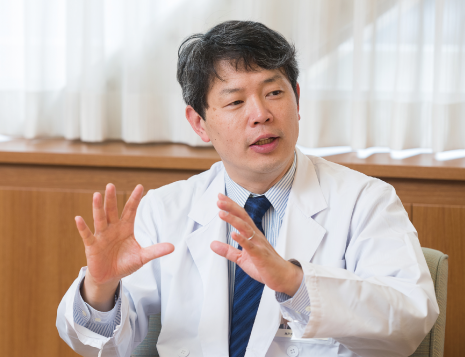

Dementia is a huge social issue, with the number of sufferers in Japan predicted to reach 7 million by 2025. Kobe University established the Dementia Prevention Project Office with the aim of contributing to society in a field where existing treatments are insufficient. With “prevention” as the keyword, the team are transforming research into social impact. This is an interdisciplinary project with participants from the Graduate Schools of Health Sciences, Medicine, Human Development and Environment, System Informatics, and the Office for Academic and Industrial Innovation. First, Professor Hisatomo Kowa introduces his program.

Basic drugs needed for treatment

What’s the status of dementia research in Japan?

Prof. Kowa:

Firstly, there are drug-based treatment schemes that aim to achieve the pattern of “Symptoms appear, visit hospital, treatment begins based on diagnosis, symptoms vanish, cure successful”. Research on dementia is quite advanced, and regarding Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type, we now have a good understanding of the process leading up to onset. Research is also progressing for a drug that removes the “senile plaque” that builds up in the brains of the patients. Mouse experiments have shown that when we administer an antibody for the formative proteins of senile plaque, the plaque is removed to some extent. This is almost certainly valid for humans too. However, after 10 years of clinical trials, the effectiveness of this treatment after symptoms develop is unproven.

Is it too late after symptoms appear?

Prof. Kowa:

Yes. Patients come to hospital after developing symptoms, when it’s too late to start treating them. The only option is to find people in pre-clinical stages (senile plaque has started to build up in the brain, but with no symptoms), and dose them before symptoms develop. But you can’t do that with conventional medical schemes.

Senile plaque buildup can be detected using an amyloid PET scan. By scanning many elderly people, we can find people who respond positively to treatment. However, the scan costs several thousand US dollars each time, so it’s not realistic. We need to be able to monitor groups of elderly people for medium to long-term periods, use a screening process to implement the amyloid PET scan, and administer the drug to those who test positive but haven’t developed symptoms.

So at the same time as drug-related research, you’ll also develop a treatment scheme for using these drugs in the future?

Prof. Kowa:

That’s right. To achieve this, we need to facilitate the understanding of elderly people, and we need to create an opportunity for regular check-ups of their cognitive functions. That’s why I’m implementing dementia prevention classes.

Cognitive care for Kobe citizens

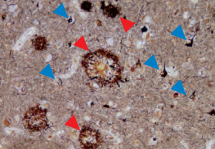

Red arrows: senile plaque; Blue arrows: changes in neurofibrils (phosphorylating tau)

What are dementia prevention classes?

Prof. Kowa:

The classes combine exercises and cognitive training with lessons about risk of illness and improving our lifestyles. We implement a program called “Brain Health Class” that incorporates various approaches considered effective in prevention. It was designed by Kobe University researchers and includes regular aerobic exercise, dual-tasks such as exercising while playing word games, and maintaining social connections. The participants join the program, we measure various markers for cognitive functions once a year, and tell the participants the results of our tests.

This initiative also helps by establishing a framework to evaluate changes in cognitive functions. To detect changes before symptoms develop, first we need data for the normal natural time course of cognitive functions – normal aging values. By analyzing participants’ data and calculating the normal time course of cognitive changes in the aged, we’ll be able to evaluate each individual by comparing them with the average.

When did the program start?

Prof. Kowa:

In July 2018, we began with 20 participants over 75 years old in a care home for the elderly in Kobe’s Kita district. It’s a 60-minute program once a week. The participants can engage in aerobic exercise and dual-task activities and receive advice about dietary habits etc. The nature of the facility allows us to monitor them long-term, and we aim to continue for 10 years.

From October 2019 we have held yoga-based special classes at the Kobe Culture Center. The participants are aged between 53 and 89, and the yoga instructor incorporates dementia prevention techniques. In the next stages we’ll introduce new options such as dance, creating a program that participants can continue without getting bored.

What’s the next step?

Prof. Kowa:

We’re collaborating with gyms and cultural centers as venues for these classes, in order to provide programs for elderly people who live at home as well as those in care facilities. We are also preparing a program with the prefectural hospital. We’re considering offering classes in hospital facilities, focusing on patients admitted for dementia risk factors like high blood pressure and diabetes. It would be ideal if we could work with local authorities to disseminate information about the classes.

A project involving the entire University

You’re also planning to make the classes a business?

Prof. Kowa:

To prevent dementia you have to engage long-term or it’s meaningless. It won’t benefit society unless we can continue without depending on research funds. We’re getting advice from Kobe University specialists on how to generate the minimum necessary funds to meet management costs – it’s not a commercial enterprise.

Photo: class at the Kobe Culture Center

You’re involved in dementia prevention with Kobe City too?

Prof. Kowa:

Based on the April 2018 ordinance to create a city adapted to dementia patients, and in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO Kobe Centre), Kobe City is creating an index to calculate the risks of developing dementia. It’s a large-scale project targeting over 40,000 people, and respondents who develop dementia will be verified using the certification level of long-term care insurance provided by Kobe City.

Can graduates and current alumni of Kobe University participate?

Prof. Kowa:

In November we started a class for alumni. For current students, we’re preparing a curriculum about dementia, with the additional aim of having them participate in research to clarify dementia risk factors. Pathological changes in senile plaque, a cause of dementia, occur over 20 years before symptoms present, so there may be risk factors that cause buildup of senile plaque based on our lifestyles when younger. We’re asking current students, faculty and staff at Kobe University to fill out questionnaires and contribute blood samples for this research. When aiming for long-term evaluation of risks, it’s important to frame it as dementia education for the whole University. By raising awareness and understanding among everyone in the University, including staff and students, I want us to become a pioneering organization in preventing dementia. This is a truly worthwhile interdisciplinary topic that encompasses the whole University.

Members of the University working together for everyone’s benefit. It’s a great endeavor.

Prof. Kowa:

Advancing our studies while organizing programs that benefit society is very meaningful. I want students to proactively participate too - if you join us with a positive attitude, you can connect with the whole University.

Different approaches to dementia prevention

Early detection using IT

Prof. Takiguchi:

Casually observing changes in cognitive functions in the everyday lives of the elderly, and linking this to early detection of dementia – this is the system at work in dementia prevention classes. We use AI speakers, and when elderly people talk to them the sensors pick up information such as voice condition, rhythm, conversation topics, movements, gestures, expressions and line of sight. We use this data to estimate the level of cognitive functions.

This is adapted from a system that formed part of my previous research on autism in children. We had a computer analyze children’s voices when they play: voice patterns, differences in pitch, inflection etc. If you can tell a child is autistic before they start school, you can provide education to fit their needs.

We’ve only just started applying this to dementia prevention. All the class participants are healthy, and we don’t know if they will develop dementia. We collect as much data as possible, and if symptoms develop after a few years, we’ll start the difficult task of verifying that person’s past data. However, many people are resistant to screening cognitive functions, so a system that can “casually” observe is very significant.

I also dream about creating a system to support the recovery of people with dementia. Communication with dementia patients can be difficult, and if we make a system supported with AI and robots, maybe they can enjoy talking more with those around them. I believe that conversation gives people a reason for living, so this is very important to me.

The importance of human networks

Prof. Kondo:

In 2015 we set up the Kobe Active Aging Research Hub. We’re engaged in research from the three perspectives of mind, body and society, with the aim of tackling issues in an aging society. I approach the dementia issue from a social sciences viewpoint - social networks can function to prevent dementia.

We’re involved in promoting communication at the Tsurukabuto Danchi housing complex in Kobe’s Nada district, and analyzing the effects. There are many elderly people living in Tsurukabuto Danchi, and some young people too, but various problems arise from lack of communication between the generations. Our project to strengthen links between neighbors has revealed the power of community. For example, the data underlines that connecting with others is more important than anti-obesity, no-alcohol and no-smoking policies when promoting health among residents. An increased sense of security within the local community can increase birth rates too. Communities are the key to solving many problems.

Data shows that dementia incidences decrease when there is a strong social network. We are incorporating this into dementia prevention classes by creating name tags, having people call each other by name, making time for conversation and holding events. We’re also cooperating with the Graduate School of System Informatics to analyze how these socials networks change.

We’re gaining an understanding of the daily lives of participants, and through the accumulation and analysis of this data, I think we will be able to suggest a concrete way of life that can decrease dementia risk. I want to look at prevention methods from this perspective too.

Note: this article is also available as a PDF in Vol. 06 of the Kobe University Newsletter "Kaze".