Researchers have revealed that praying mantis (mantids) infected with parasitic hairworms are attracted to horizontally polarized light that is strongly reflected off the surface of water, which causes them to enter the water. In a world-first, these research results demonstrate that parasites can manipulate the host’s specific light perception system to their advantage, causing the host to behave in an abnormal manner.

This discovery was made by an international research group consisting of Graduate student OBAYASHI Nasono, Associate Professor SAKURA Midori and Associate Professor SATO Takuya of Kobe University’s Graduate School of Science, Associate Professor IWATANI Yasushi (Faculty of Science and Technology, Hirosaki University), Professor TAMOTSU Satoshi (KYOUSEI Science Center for Life and Nature, Nara Women’s University) and Dr. CHIU Ming-Chung (National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan).

These research findings were published in the American scientific journal ‘Current Biology’ on June 21, 2021.

Main points

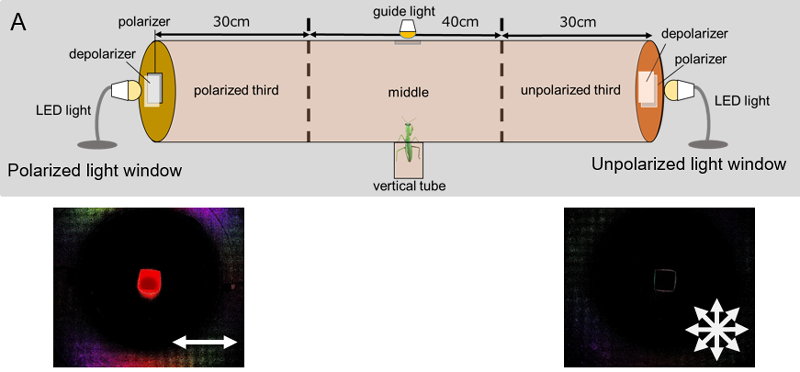

- The hairworm parasite lives inside the body of an insect host (such as mantids and crickets) that typically inhabits forests and grasslands. When the hairworm reaches maturity, it induces the host to enter water (including ponds and rivers), where the hairworm breeds, thus completing its life cycle.

- How the hairworm causes its host to enter the water has mystified researchers for over 100 years.

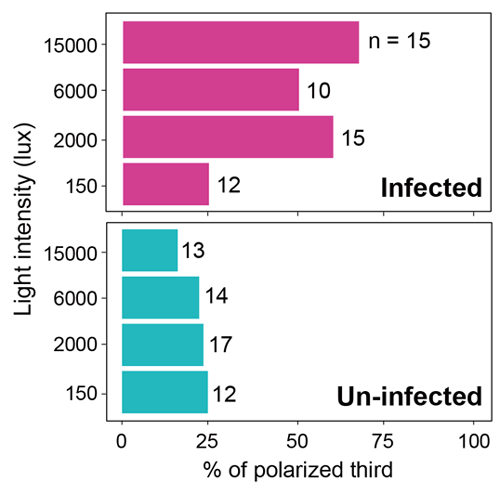

- A two-choice experiment conducted in a laboratory revealed that a higher percentage of mantids infected by a hairworm were attracted by horizontally polarized light*1 compared to uninfected individuals.

- In the outdoor experiment, a higher number of infected mantids entered the deep pool that strongly reflected horizontal light than the shallow pool that reflected weakly polarized light.

- There is a strong possibility that hairworms induce the host to enter the water by manipulating the host’s perception of horizontally polarized light.

Research Background

Normally, an animal’s morphology and behavior are regulated in order to benefit the individual’s survival and reproduction. However, approximately 40% of terrestrial organisms are parasites and it is said that all wild animals have at least one type of parasite. In other words, various anatomical changes and behaviors observed in wild animals could be strongly influenced by parasites. Remarkably, there are many species of parasite that can alter aspects of their host’s morphology and behavior (host manipulation) for their own benefit (i.e. to increase the parasites’ fitness). Parasites that manipulate their hosts are a good example of an extended phenotype*2 and have come to fascinate many biologists.

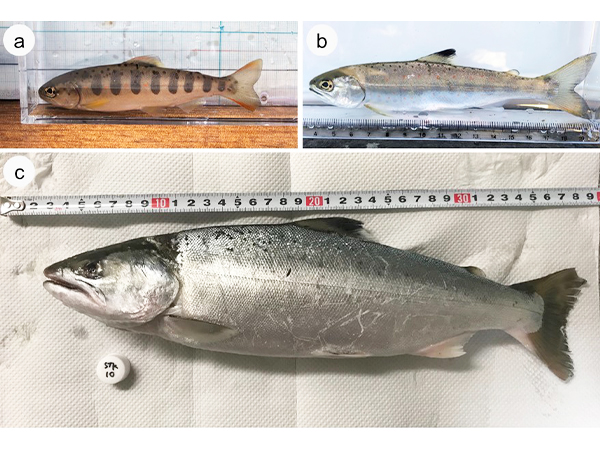

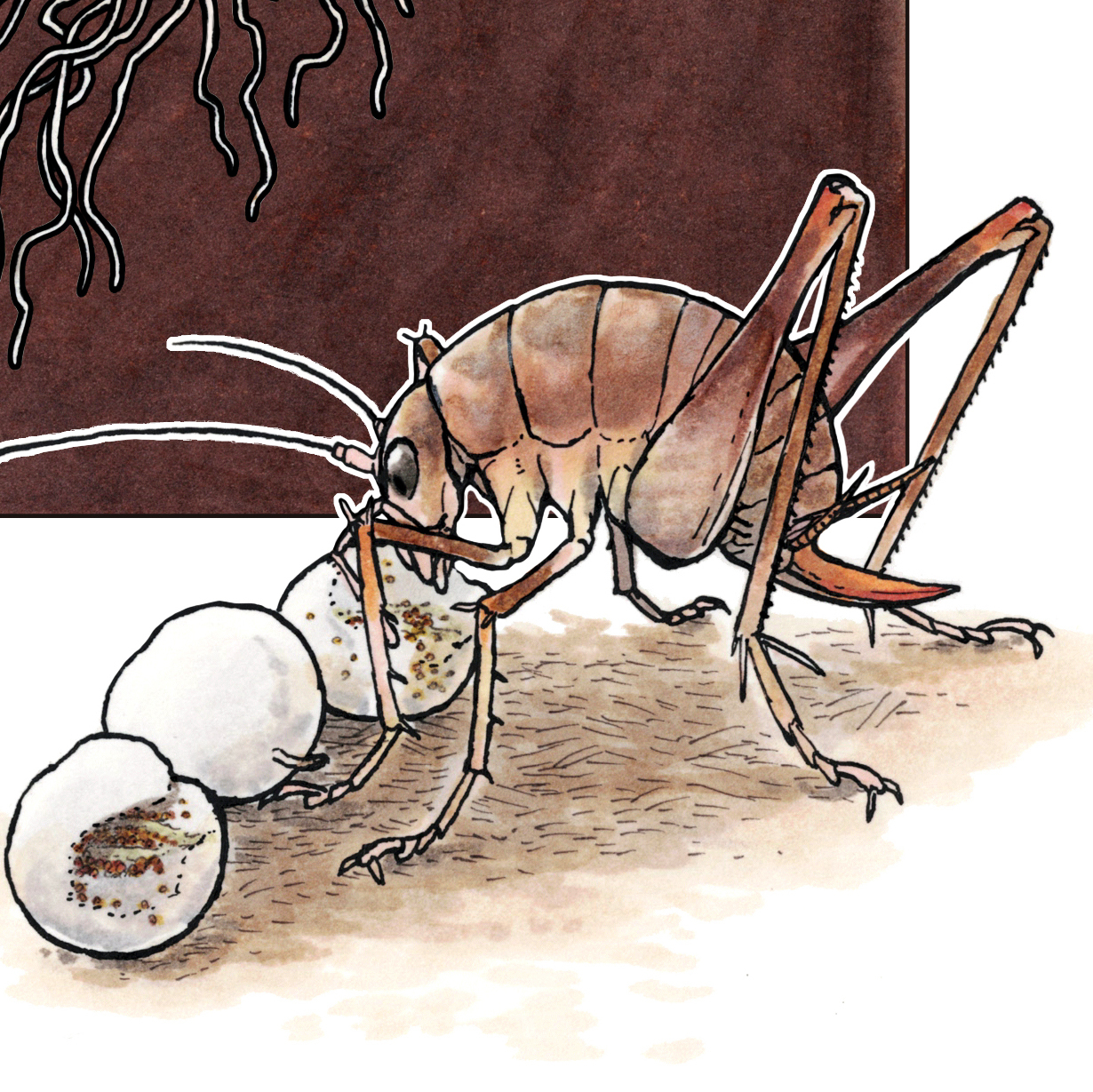

A known phenomenon whereby the parasite manipulates the host’s behavior can be seen in hairworms. Hairworms are nematomorph parasites that live inside insects such as mantids and camel crickets (referred to as the ‘host’). However, hairworms reproduce in rivers and ponds, so in order to move themselves into these environments, they manipulate the host so that it jumps into the water (Figure 1). Previous research has suggested that the brightness of reflected light (light intensity) on the surface of the water attracts the host, causing it to fall in. However, aside from the surfaces of rivers and ponds, there are many other luminous environments and instances in nature, including forest openings, bright sandy habitats and grasslands reflecting sunlight or moonlight. If the host were attracted to every single occurrence of bright light in nature, then the host manipulation would fail. Therefore this behavior of entering the water cannot be sufficiently explained in terms of mere attraction to the light.

After hatching in the water, hairworm larvae parasitize aquatic insects and form a cyst in the hosts’ body cavity. After the aquatic insect has grown wings, the hairworm is transported from an aquatic environment to a terrestrial environment. If the aquatic insect is consumed by a mantid, the hairworm grows inside the mantid’s body until it reaches maturity and causes its host to enter the water. Once the mantid is in the water, the hairworm escapes back into the aquatic environment to reproduce, and its lifecycle ends.

Polarized light*3 is a type of light where the electric field of the light wave oscillates in only one direction. The light reflected off the surface of a body of water contains a lot of horizontally polarized light, and it has been shown in recent years that many arthropods use this horizontally polarized light to either seek out or avoid water.

The researchers hypothesized that host, manipulated by the hairworm, is attracted by the horizontally polarized light and enters the water.

Research Methodology and Results

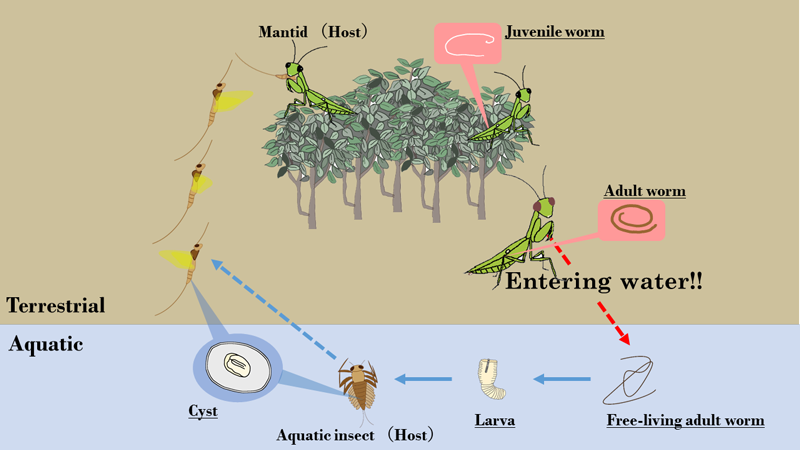

To investigate this hypothesis, the researchers began by conducting laboratory experiments to see whether or not mantids (the Asian praying mantis species Hierodula patellifera, hereafter referred to as ‘infected mantids’) infected by a hairworm parasite (Chordodes sp.) and uninfected mantids of the same species would be attracted to horizontally polarized light. The experiments were conducted using a cylinder divided into three sections, with a polarized light section at one end and an unpolarized light section at the other end (Figure 2). The mantid was placed in the middle section, and its location was recorded after 10 minutes had elapsed (i.e. whether or not it had moved into the polarized or unpolarized light sections). Over the course of these two-choice tests, four different strengths of light were used (these corresponded to twilight: ~150 lux, cloudy weather: 2000 and 6000 lux, and sunny weather: 15,000 lux) to investigate whether the brightness affected the percentage of individuals attracted to the polarized light.

By changing the direction of the polarizing plates, the researchers set up a two-choice test for the mantids of either horizontally or vertically polarized light.

The results revealed that a higher percentage of infected mantids chose the polarized light compared to uninfected individuals (Figure 3). Among the polarized light choices, there was a particularly high tendency for polarized light of over 2000 lux to be chosen. Conversely, mantids did not tend to choose the polarized light section if the angle of polarization was changed to vertical, regardless of the strength of the light and their infection status. From these results, it can be concluded that mantids infected by hairworm parasites are attracted to horizontally polarized light.

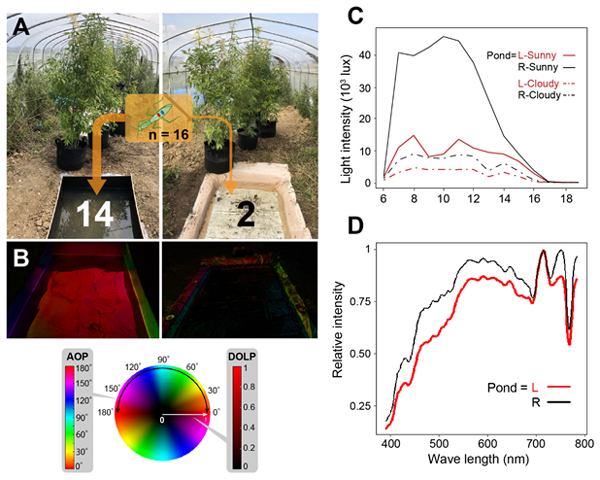

14 individuals entered the pool on the left. (A): Compared to the right pool, the horizontally polarized light reflected off the surface of the left pool was stronger (B) and the light intensity was weaker (C). The spectrum of the light reflected in each pool was similar (D). Panel B is an image of polarized light on the water’s surface. Red indicates that the angle of the polarized light was close to horizontal, and high saturation indicates a high degree of polarized light.

Next, the research group conducted outdoor experiments to investigate whether or not infected mantids would jump into a pool reflecting strong, horizontally polarized light. The experiments were conducted in a cultivated area belonging to the Food Resources Education and Research Center, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Kobe University. A mesh enclosure was set up containing two pools: Pool A, strongly reflecting horizontally polarized but dim light (low light intensity), and Pool B, where the surface reflection was brighter (strong light intensity) but weakly polarized (Figure 4).

The researchers released the infected mantids into a tree located in-between the two pools and observed the insects’ entry into the water via video footage captured by stationary cameras.

Among the 16 infected mantids that exhibited this behavior, 14 individuals entered Pool A, which strongly reflected horizontally polarized light (Figure 4). Therefore based on the results of both the laboratory and outdoor experiments, it can be concluded that infected mantids are induced by the horizontally polarized light to jump into the water.

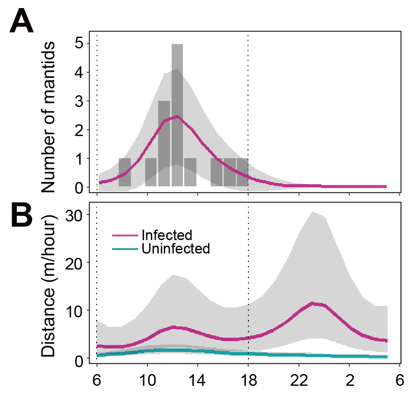

The curves and grey areas in each graph represent the 95% confidence interval estimated by a statistical model.

Another interesting discovery made by this study is that many infected mantids entered the water at around midday (Figure 5A). In the laboratory experiments, the distance walked by mantids was measured and it was found that infected mantids walked more during noon (Figure 5B). This presents a new possibility that the circadian rhythm of the host or the parasite may be involved in increasing both the host’s attraction to horizontally polarized light and the host’s level of activity, which ultimately induce water-entering behavior at a specific time of day.

Research Significance and Further Developments

In nature, animals have evolved diverse abilities to perceive the intensity, color, shade and polarization of light. These research results show, for the first time in the world, that parasites can skillfully manipulate these abilities to cause the host animal to exhibit behaviors that benefit the parasite.

This research group has recently begun investigating what kind of mechanism uninfected mantids have for perceiving horizontally polarized light. They are also trying to work out how hairworms manipulate this mechanism. Illuminating these aspects will not only enable us to understand parasitic behavioral manipulation but could also contribute towards the development of new methods for controlling animal behavior.

Glossary

*1 Horizontally polarized light

Linear polarization is when the electromagnetic waves of light only go in one direction (for example, horizontal or vertical). Light reflected off the surface of water contains horizontally polarized light. Bodies of water reflect a greater level of horizontally polarized light the deeper and darker the bottom is.

*2 Extended phenotype

The main idea of this biological concept is that an individual organism’s genes do not only effect the individual’s morphology and expressed behavior, but have an extended impact on other individuals and the surrounding environment. Through host manipulation, a parasite’s genes affect the host’s morphology or expressed behavior. This is an example of an extended phenotype.

*3 Polarized light

The light that radiates from The Sun is unpolarized. However, when this light is reflected (for example, by molecules and objects above the atmosphere or by the surface of a body of water), the direction of some of the electromagnetic waves becomes linearly polarized (i.e. they run in one direction), resulting in the light being polarized to a degree.

Video

Illustrated explanation of the research results and comments from Kobe University’s Obayashi Nasono and Associate Professor Sato Takuya: Enhanced polarotaxis in hairworm’s host manipulation/ Curr. Biol., June 21, 2021 (Vol. 31, Issue 12) - YouTube.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out with funding from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants (19K22457, 19H04925, and 19H04934) and Kobe University’s Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research.

Journal Information

Title

DOI

10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.001

Authors

Obayashi, N., Iwatani, Y., Sakura, M., Tamotsu, S., Chiu, M.C. & Sato, T.

Journal

Current Biology